Leonor Taiano, Ph .D.

“The bosom of America is open to receive not only the Opulent and re-spectable Stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions; whom we shall welcome to a participation of all our rights and privileges, if by decency and propriety of conduct they appear to merit the enjoyment.”

From George Washington to Joshua Holmes, 2 December 1783

In the last years, migration problems have become a key issue for countries all over the world. In Europe and the Americas, far-right populist parties continue to stoke the popular backlash against migration. Matteo Salvini, Giorgia Meloni, Éric Zemmour, Marine Le Pen, Rocío Monasterio, Viktor Orbán, Andrej Babiš, among others, continue to hammer on anti-immigrant sentiment, hoping it will remain a potent issue in up-coming elections. In the specific case of the United States of America, its status of “nation of immigrants” is being challenged by ideologies that reduced some immigrants to the stereotype of “bad hombres” or “beard-ed terrorists”. Donald Trump, Marco Rubio, Ted Budd, Herschel Walker, Blake Masters, Katie Britt, Adam Laxalt, Donald Bolduc, James Lankford, Tim Scott, and J.D. Vance are the promoters of a dangerous anti-migrant sentiment. The post-racial America has become a fallacy due to a xeno-phobic propaganda that assigns to “the other” an antagonist role.

Nowadays, Joe Biden’s migration policy has already rescinded many of Donald Trump’s controversial entry ban on citizens of Muslim-majority countries, halted construction of Trump’s wall, reafirmed protections for DACA recipients and promised a more comprehensive approach to ad-dressing the root causes of the migration crisis. In the fiscal year 2021, the US Border Patrol confirmed more than 1.6 million encounters with migrants along the US-Mexico. In 2023, Biden announced a program to strengthen the admission of immigrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, while at the same time his administration will crack down on those who fail to use the plan’s legal pathway and strengthen border security.

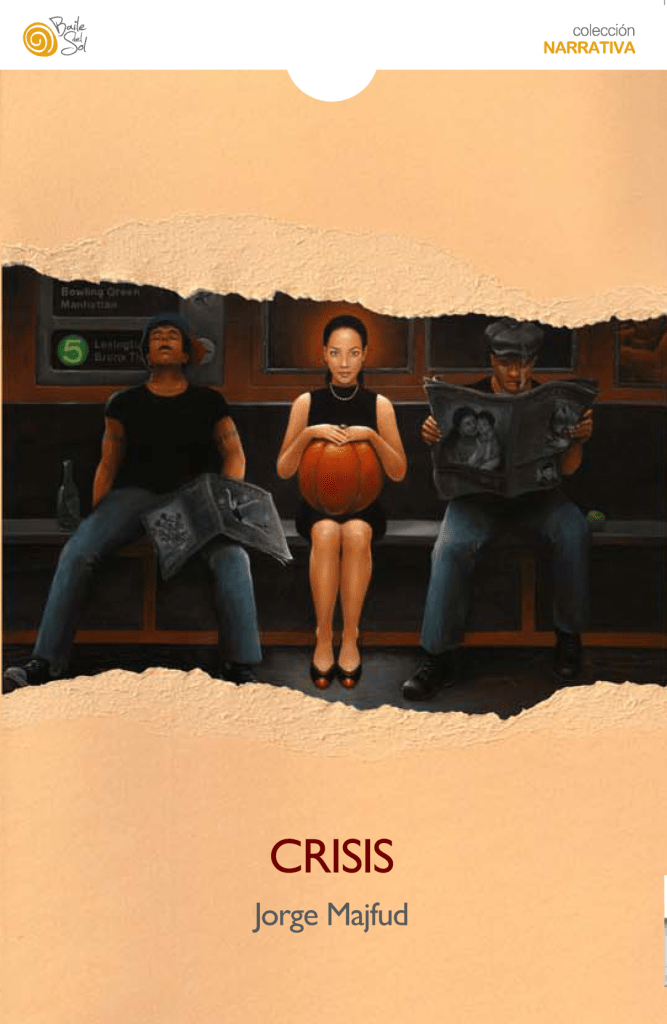

I refer to the current context of migration because the purpose of this research is the analysis of Latin American immigrants’ situation in the United States through their fictionalization in Crisis, a novel written by the Uruguayan Jorge Majfud. My goal is to seek the portrayal of Majfudian characters as archetypes of Latino American immigrants in the United States of America. This research is not devoted to explaining the causes and effects of migration in a politically biased manner. It only expects to reconstruct how Crisis reflects the current “Latino issue” in the United States. Therefore, even if I mention some aspects that allude to the possible shared responsibility of American hegemonic policies and Latin American corruption, my study is moving beyond that query to examine the aspects that make the Latino immigrant the antihero of the post-heroic society. To perform this task, I have tried to answer the following questions: how are Latino immigrants portrayed in Crisis? What is the role that Americans of Latino descent have in Crisis? Is there any connection between the geopolitical context and their migration? How does Jorge Majfud fictionalize his perception of reality?

1. Crisis: Juxtaposition of Hispanic Stories

Crisis is a mosaic novel in which Jorge Majfud gathers a series of stories about Latin-Americans, specifically Hispanics, who migrate to the Unit-ed States, as well as stories about Americans of Hispanic descent. The novel is constituted by a juxtaposition of stories, selected by date, place (different localities from the USA), and the Dow Jones Industrial Aver-age (Pérez Vega). The last element highlights the relevance of capitalism as the only determining factor with regards to the quality of life, while the different locations emphasize the wandering life of undocumented immigrants (García-Teresa, 127). According to its content, the text could be divided into three thematic areas: Socio-political and philosophical re-flections about migration, stories of Latin-American migrants, and stories of American citizens of Latin-American descent. Consequently, the first thematic area includes a series of remarks about the global mass society and the dangers of a global inequality that is taking place through international relationships of supremacy and subordination. The second thematic area includes situations that allow for exploring Latin American migrant’s’ everyday life in “the country of Uncle Sam”. The third thematic area is related to the social function that Americans of Hispanic descent have of their country of birth. Furthermore, Jorge Majfud also carries out socio-moral observations that contribute to the understanding of these current times of social and financial straits. Crisis is a revolutionary book, a gloomy tableau about a downward spiral produced by the pragmatic Manicheism of globalization, which, according to Majfud, reduces to the category of inferior or negative everyone who does not correspond to the social mechanism of the new planetary civil society. The novel reproduces reality through a concatenation of events between the personal story of its characters and the geopolitical context of the Americas. Its characters portray the struggle for integration and the survival in a foreign land. There is no space for a fantastic dimension in Crisis; the novel is a kind of analytical and visionary realism. Jorge Majfud makes visible a fact that many “no committed readers” try to ignore: the chaos produced by inequality and social unfairness. Although the narrator mentions every char-acter citizenship and ethnic group, Crisis promotes a collective Hispanic identity, whose foundations reside in having a common language, which differs from the host language spoken by the WASPS. Spanish versus English becomes a symbol of identity and segregation within the novel. Latin Americans cannot be included within the “American community”. Their historical memory is heterogeneous from the American ethnic model of nation, which stresses the importance of Anglo-Saxon background as a reference for the American vernacular culture. Latin America colonial past and their use of Spanish as their first language plays a central role in their reduction to the category of ethno-linguistic population in the Unit-ed States of America.

La lengua es un factor más importante de lo que parece […] El idioma es memoria viva. En ninguna otra parte del mundo uno puede sentir, como en Estados Unidos, que el español es la patria […] (Majfud)

In fact, the relationship between the USA and Latin America places His-panic migrants in a prickly sociocultural position. The expressions spic, greaser, wetback, wab, pepperbelly, orange picker, border bunny, border hopper, border rat, Cans, Bans, Latrino, Beaner, among others, circum-scribe a linguistic and racial limit that categorize Hispanics as inferior, because their origins are different from the “WASP” ideal. Therefore, they often live on the edge of the society that is “hosting” them, “confined” in Hispanic neighbourhoods, which are a visible manifestation of poverty and social problems. In this way, Majfud expresses an explicit viewpoint with regards to the crisis. His interpretation of the polemical questions about migration condemns the deep gap created by the relationship centre-periphery, namely Anglo-American versus Hispanic-American. In-deed, the United States of America performs a fundamental role within Crisis. The novel reflects on “the real world of the American fiction” by means of the vicissitudes experienced by men and women who are aware of being aliens to a place in which the opposites coexist: wealth and misery, respect for life and the death penalty, the search for peace and the business of war, cosmopolitanism and localism, and religion and materialism.

Si hay en el mundo un país que es asociado casi por unanimidad con el materialismo ese es Estados Unidos. No obstante, dice Susana, si com-paramos este país con cualquier otro en América Latina, en Asia o en Europa en ninguno encontraremos tantas iglesias y en casi ninguno tantos asistentes a los templos de Dios los domingos. Particularmente en el sur, la gente no pregunta si crees en Dios o si tienes iglesia, sino a qué iglesia vas cada semana. No poseer un auto o no tener una religión con su respectiva iglesia hace derivar las miradas de los curiosos. Nadie es tan pobre en Estados Unidos como para no tener un auto y una religión. (Majfud, 51)

Consequently, Crisis analyses migration from a perspective marked by the sophism of globalization. Its characters exemplify the role of the Latin American migrant in a system marked by paradoxical hegemonic policies. Crisis aims to demonstrate that Hispanic immigrants are being penalized by the failure of a unified economic framework that generates economic depressions and inequality. In fact, Jorge Majfud begins by criticizing the abstract concept of capitalism per se in order to indicate its consequences in the Hispanic diaspora. The Uruguayan author insists on the fact that “Hispanos” are tools of a competitive economic process that involves the rise of productivity and the lowing of wages to increase the power of in-visible hands that monopolize the overall global wealth. It is obvious that the author considers that American democracy is a fallacy; in fact, he goes far beyond Robert Dalh’s definition of Global Poliarchy (Dalh, 35–40) and supports the thesis that the whole world is under the yoke of the dictatorship of capital (Tubbs). Consequently, Majfudian characters are part of a submissive and disciplined flock whose cornerstone is capital and economic hierarchy. The lack of individuality within a society in crisis is, according to Jorge Majfud, a socio-philosophical message that could be summarized in one simple phrase: “the human race cannot modify reality”. As a result, the immigrants who appear in Crisis, including those who wish to fight against injustice and poverty, do not have the power to be themselves; they are just playing a social role.

Y también los olores y los cuadros y los pisos de cerámica y el paisaje por la ventana y la chica que aparecerá y te sonreirá. Será siempre esa misma sonrisa que irá incluida en el mismo menú y al mismo precio y no te importará porque sabrás que estás pagando para que te sonría, amable, linda, casi como si te simpatizara. Como si te conociera. Porque en el fondo ya te conoce. Te ha sonreído antes en otros rostros como el tuyo que para ella es el mismo rostro. Y en el fondo sabrás que no es sincera, pero ella no lo sabe y a ti tampoco te importará […]. (Majfud, 13)

Accordingly, it is revealing that most of Crisis’s characters come from countries that have been intervened by the USA. It is easy to understand that without mentioning the belief of Manifest Destiny or the notion of Empire of liberty, and without alluding to the expressions like Big stick, Anti-Communist Struggle, drug traficking, commodity smuggling, the War Against Terrorism, the Struggle Against Left-Wing Populism, Jorge Majfud introduces migration as a consequence of American expansion-ism. It is clear that the Uruguayan writer adopts the theme of Ameri-can interventionism, which was previously stressed by Eduardo Galeano (9–17) and Noam Chomsky (2015) and supports their ideas about the responsibility of USA in the destabilization, poverty, and human displacement in Latin America.

HUNTER: … luego, muchos años después en El Salvador, un presi-dente republicano, Ronald Reagan, brindó una barda para protegerlos mientras tenían elecciones libres, que trajeron la libertad a ese país. Fueron dos partidos distintos, pero estoy hablando del partido de la libertad, el Partido Republicano. (Majfud, 25)

Although Crisis promotes the idea that Latin-American socio-political structure has been largely led by the Northern Power and among its char-acters there are not victims of Castro’s regime, the novel does not deserve to be regarded as biased. In fact, Crisis does not consider American Capitalism as the absolute evil but conceives the contrast Capitalism-Socialism as a fallacy that served to reinforce an international political mafia through the creation of enemies used as a tool for the manipulation of the masses, including those from Latin America. As a matter of fact, in its search for objectivity, Crisis blames Latin American puppet regimes, which without any patriotic purpose, subdued Latin America to the despotism of capital by using pretexts that bring with them financial fragility, the dismantling of local industries, the denaturalization of state enterprises and social inequality (Goldhamer, 15). As an example, the novel refers to the policies adopted by the Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who was responsible for the fading of more than a thousand parastatal companies and the disappearance of the Rural Credit Bank (Urzúa, 48–56). In Crisis, Salinas is the paradigm of the Latin American ruler who supports the informal colonization and turns a blind eye to the local mafias.

Hace una punta de años que estoy de este lado. Me vine después de Salinas. Mi pueblo no existía en el mapa hasta que llegó él. Vivíamos de hacer camisas y pants. En el pueblo todos tenían una maquinita de esas que hacían los puntos y vivíamos bien. Hasta que dijeron que el presidente iba a pasar por Guanajuato y alguien tuvo la linda idea de invitarlo para que viera el progreso del pueblo. Y cuando Salinas vio que trabajábamos lindo mandó a que nos cobraran impuestos […] lle-varon chinos al pueblo […] Así que si esto salías doscientos pesos los chinos lo hacían por cincuenta. Después puse un puestito de tacos y refrescos y me cayó la familia, diciendo que tenía que pagar mil pesos por la protección […] Yo me reí hasta que un vecino me dijo que ya había muerto uno así, que mejor les pagara. Y ¿de dónde iba a sacar yo si recién empezaba? Todo eso terminó de liquidar el trabajo en el pueblo y tuve que venir […] (Majfud, 71)

In this context, marked by the local clientelism and globalization, Crisis recalls that migration is simply one of many strategies to find an antidote to counteract the disastrous metamorphosis that Latin America is under-going due to vested hegemonic interests (Hytrek, 3-6). In fact, while the local Latin American elite profits from globalization; the ordinary citizens are forced to migrate and become part of the “Latin American transmigration” to the USA (Trigo, 13–30), which is characterized by its uncertainty and segregation.

2. The Hispanic Antihero of the Post-heroic Era

Unfortunately, the merger between the American paradox and the corruption of Latin American governments makes of the Latin American migrant a being bereft of extraordinary qualities. Even if his life journey has characteristics that, since the classical era could be attributed to the hero who begins an expedition in search of the promised land, his pilgrimage towards hostility does not make of him an expert of the world, but reafirms his condition of the subordinate victim. Indeed, even if the “Hispano” crosses the desert, fights against the monsters of labour abuse and inhuman laws, his displacement does not represent a cognitive journey. It only leads to the disregard of individuality and the assimilation to the stereotyped “Latino” mask. In fact, even if many of “Majfudian immigrants” could be considered a modern version of Ulysses, an archetype of the individual who wanders about by sea and land in a pilgrimage that seems a punishment. The dificulties faced by Crisis’s characters are not proofs that enable them to confirm their own dignity, intelligence, or ability to overcome adversity. They are simply the evidence of a materialistic determinism, which gives them the role of the unfortunate post-heroic Ulysses, whose arrival took place when the USA has already created its founding myths based on the Anglo-Saxon Protestant identity that tries to erase the Hispanic-Catholic past that, by a question of postcolonial inheritance, the Hispanic American immigrant represents (Taiano, 123–148). Consequently, through the stories of Latin American migrants, Crisis recalls that the crossing of the Mexican-US border is not characterized by the rain of Manna from heaven. Latin Americans do not find the Land of Milk and Honey, the Río Bravo does not open like the Red Sea, and there are not magnanimous signals to show that Latinos are God’s chosen people. The God of Latin Americans does not lead his people to the victory or liberation but drives them into legal persecution. In fact, the only support that they can find are the bottles of water left by the Helping Immigrants and Refugee Organizations.

El sábado 3 a la tarde tropezó con una botella de agua caliente, de esas que los perros hermanos tiran sobre el desierto a la espera de salvar algún que otro moribundo.

El domingo se durmió […] con la esperanza de no despertar […]. Pero despertó […]. Enseguida sintió el temprano rigor del sol, otra vez en su lento trabajo de chupar de su piel y de su carne y de su cerebro el agua que le había ganado a la suerte del día anterior. (Majfud, 11)

This life of violence persecutes every Majfudian character. In fact, Crisis tells the stories of immigrants who seem to unfold the same general pattern of failure. They are unfulfilled antiheroes who experience a sense of frustration. Their migration appears doomed, unable to be resolved happily. Every story works up to a climax of self-destruction, the American Dream always finishes in a nightmare. Even if there are some cases in wich the story begins with some kind of “hope” and dream-like success, the characters will fall into an inexorable climax of destruction.

Pero de a poco todo fue cambiando. En dos meses había juntado para el pasaje de Lupita, pero luego vino la crisis y el primero en volar antes de que el restaurante cerrara fui yo, porque era el nuevo, me decían […]

Yo no dije nada pero ella [Lupita] terminó subiendo atrás seguro que contra su propia voluntad. Y cuando arrancó la camioneta ella me hizo así con su manito y me tiró un beso triste. Yo sabía que iba llorando porque la conozco. Yo sabía que eso no iba a funcionar ni esta puta vida iba a funcionar. (Majfud, 37)

In Crisis, migration always turns to disaster. Migrants cannot overcome the mighty foe of globalization, which, according to Majfud’s characters, is the centre of dark and destructive powers. Their initial “dream stage” is only the preamble for a stage of frustration and total loss. There are condemned to play the tramp role to learn that they have no options, no freedom, and they cannot flee from their condition of orphans of the con-temporary world.

En pocas semanas se levantó el tendal de carpas de Sacramentillo y nos vinimos con Ricardo con la promesa […] de que era por pocos días hasta que Obama sacara a los deudores de los foreclosures y nos devol-vieran la casa de Santa Bárbara que tanto nos había costado. Ricardo decía que no nos había costado mucho porque no habíamos pagado ni el tres por ciento […] nos vendieron un plan que podríamos pagar con el sueldo de Ricardo. Pero como subieron las cuotas como locos y no pudimos pagar unos mesitos, nos mandaron con perro y todo afuera […]. (Majfud, 51)

In fact, Jorge Majfud remains sceptical about the possibility that Latin Americans attain their integration in the United States. This country ap-pears as a flawed society built precisely upon the impossibility of reaching the American Chimera, which is the abiding subject of Crisis. The novel is a response of the Latin American migration drama; its characters will not be promoted from rags to riches. The American promise of “liberty and justice” does not apply to Latinos; their success in the “land of Uncle Sam” is impossible; their migration will only accelerate their devastation. In fact, Crisis illustrates though its microcosm, as Upton Sinclair did in The Jungle (Mattson), that Latinos are exposed to the inhumanity of capitalism, which leads to the disparity between the American Illusion and the American Experience.

3. The Hybrid Existence: Americans from Hispanic Descent

In keeping with the foregoing, Crisis also examines the complex case of American citizens of Hispanic descent. The novel expresses that they need to undergo a process of Americanization and Dehispanization to become effective members of the land of their birth since their status of native-born Latino constitutes a social disadvantage. In fact, the novel reflects on the questions of cultural identity, nationhood, and ethnicity, since its American from Hispanic descent characters live what could be defined as a hybrid existence. Their double culture or, more precisely, their dual identity has a catastrophic impact on their daily lives, making it dificult their total integration to the American society. Such is the case of the character called Nacho Washington Sánchez, who lost his life in a Latin American party. Nacho was a Chicano who went back to high school after spending much of his adolescence as a worker in a poultry-breeding factory. Without doubt, Nacho is one of the most revealing characters of the novel. He is someone who finds it dificult to assume his role of American citizen due to his ethnic identity and the legal-social status of his parents. In fact, his crisis comes from his decision of defining himself according to his ethnicity and not by his place of birth. Ius soli versus Ius sanguinis, this is his sad dichotomy.

Todos sabían que los padres de Nacho eran ilegales y no habían salido de esa desde que el Nacho tenía memoria, por lo que él mismo, sien-do ciudadano, evitaba siempre encontrarse con la policía, como si lo fueran a deportar o lo fueran a meter preso por ser hijo de ilegales, cosa que él bien sabía que era absurdo pero era algo más fuerte que él. Cuando le robaron la billetera en el metro al aeropuerto no hizo la denuncia y prefirió volverse a casa y perdió el vuelo a Atlanta. Y por eso uno podía decirle lo peor y el Nacho se quedaba siempre en el molde, mascando rabia pero no levantaba una mano, que mano y fuerza como para doblar un burro no le faltaba. No él, claro, él no era ilegal, era ciudadano. (Majfud, 30)

While Nacho represents the individual, who does not define himself as an American citizen, George, his killer, rejects his Mexican identity in spite of his ethnic background. The young murderer is unduly influenced by the image that American society has of Hispanics and relegates his cultural inheritance. In fact, George, like other characters among which we can include those that the narrator calls “las Niurka Marcos” and “las Jennifer López”, is a product of an Americanising Alchemy, which induces to adopt an “American mask” to become a kind of hegemonic homun-culus (Taiano, 123–148).

No, no lo queríamos matar, pero él se lo buscó. ¿Qué delito hay peor que abusar de una niña? No la manoseó, pero así empiezan todos ellos. Ellos, usted sabe a quiénes me refiero [a los mexicanos]. ¡Ellos! No fuerce mi declaración, conozco mis derechos. Ellos no saben respetar la distancia personal y luego pierden el control. No, mis padres eran mexicanos pero entraron legales y se graduaron de la universidad de San Diego. No, no, no… Yo soy americano, señor, no confunda. (Majfud, 31)

Moreover, Jorge Majfud highlights that many times the relationship between second-generation Americans and their land of birth is marked by the deplorable service they offer as “intermediaries” between the United States of America and the Latino immigrants. According to Majfud’s perspective, the relationship between the USA and its homunculi is very close, because their character has been shaped to turn them into defenders and guards of their country. In fact, in Crisis “las Niurka Marcos” and “las Jennifer López” play the role of persecutors of undocumented migrants.

La mujer de la Migra las estaba entendiendo desde el comienzo ¿Cómo no se habían dado cuenta, con esa cara de Niurca Marcos? El problema de las Niurca Marcos es que nunca se sabe si son latinas o americanas […]. No tienen acento cuando hablan inglés […], pero entienden hasta los más sutiles insultos en español. Pero si te las imaginas sin el unifor-me y con el pelo sin teñir y sin los lentes de contacto celestes, ensegui-da te das cuenta de que son como nosotras. Por eso las contratan y por eso ganan tanta plata, son imprescindibles a la hora de cazar ilegales. (Majfud, 77)

In Crisis, most of the Hispanics born in the USA are not simply villainous, but rather tragic in their self-destructive pursuit of justice and respect for authority. Their chauvinism is deprived of reflective thought. As Javert in Les Misérables (Bellos), they are the most tragic legalists of American society, since they perceive themselves to be excluded from a system that closes its doors to those who do not belong to the WASP archetype. Consequently, they develop an irrepressible hatred for their ethnicity and opt to become “Latino illegal persecutors”.

Cuando llegaron al departamento de policía clasificaron a las obreras en distintas secciones. En un cuarto impecable, como el del doctor Durham, una mujer parecida a Jennifer López le indicó que se desnudara después de sacarse de encima todos los personal stuffs. (Majfud, 76)

Besides presenting characters who fully align themselves with their Lat-in-American ethnicity and characters who deny or feel shame of their Hispanic backgrounds, Crisis shed light on one of the saddest aspects that can be attributed to the alleged integration of young Americans of Hispanic descent: become the new cannon fodder for interventions in the Middle East. This latter subject is represented through the story of Tony Gonsález, a Hispanic soldier maimed by a grenade blast in Iraq. Tony is more unfortunate than George is, because he did not only have to cut off his Spanishness to afirm his American identity. He also had to mutilate his body to become a “hero” of post-heroic America. He sacrificed his physical and mental integrity to be paid with a Silver Star Medal.

Pero se enojó un día que me escuchó decirle a María José que no entendía por qué no le habían dado la de oro, siendo que arriesgando su vida salvó a cinco compañeros de armas de una muerte segura. La loca de María José, que es una liberal amarga, egún Tony, había dicho o había sugerido, que de no ser latino hubiese recibido la de oro. (Majfud, 46)

Tony Gonsález, who clearly shows signs of Post-traumatic stress disorder, struggles to give a new meaning to his life after being maimed in Iraq. His story demonstrates that young Hispanics have taken the place that during the Vietnam War was hold by Anglo-Americans who belonged to the working class. Gonsález is the proof that the veteran rights activists’ struggle gave a big lesson to American authorities: Latinos are those who must be recruited to fight in the war, not the American white working class.[i] In addition, without mentioning the Dream Act (Lee, 231), Crisis recalls that war also represents the possibility of becoming legal for many undocumented Latinos who grew up in the United States, such is the case of Robert González, who embodies those who in “the real life” are in his situation. In fact, this character incarnates another American Paradox that consists of the fact that, while the Pentagon is looking for young undocumented immigrants to enlist in the military, other undocumented workers are being persecuted and deported.[ii] Young “Hispanos” have become the target for recruiters because, according to Jorge Majfud, war exteriorizes social discrimination and causes stigmatizations that characterize American society. Consequently, in Crisis war is conceived as a tool to perpetuate and confirm the American social strata. In the same manner as the Anglo-American working class young men were manipulated by war recruitment slogans and demagogical speeches during the Vietnam War, young Latinos are becoming victims of brainwashing that makes them think that war is the only way to afirm their pertinence to the USA. Therefore, they adopt a blind chauvinism that hampers them to realize that they only integrate the troops exposed to danger in international conflicts.

4. Conclusions

It is incontestable that, since its first pages, Crisis carries out a profound and provocative reflection about the relationship among geopolitics, globalization, and migration. The novel blames international politics and the global economy as generators of the Latin American exodus. As a matter of fact, Crisis includes theories that explain the congruity among these two factors and migration through an objectivist interpretation of the characters’ subjective reality. At the same time, the novel introduces sociological and philosophical reflections that show echoes of social protest or proletarian literature. It is precisely through its committed intention that the novel alludes to the social-political battles that marked the 20th-century and preannounced the 21st-century crisis. The book adopts an ideologically explicit strategy of writing that, from my perspective, could include Jorge Majfud within the committed group of authors who write about the Latin American 21st-century immigration to the United States. His commitment expresses the dificult relationship between the idiosyncrasies of the “Latin American guest” and the “An-glo-American host”. Consequently, it is possible to conclude that its importance lies in the fact that it was written at an opportune moment. Crisis deciphers the causes of transmigration not only by alluding to the American interventionist policies, but it also blames the corruption of Latin-American governments. In fact, the novel recalls that, in the specific case of Latin American countries, globalization only benefits local elites and leads to the marginalization of ordinary folk whose only alternative is migration. The exodus of Majfudian characters states that Latin-Americans migrants have become the antiheroes of globalization, their tribulations only serve to afirm their role of subordinates of global determinism.

In the specific case of undocumented migrants, they symbolize the defeat of a people whose “Moses”, namely the coyote, is an antihero who cannot escape his subjected condition in a dystopian society. With this perspective, Jorge Majfud identifies the social roots of undocumented migrants’ vulnerability and their impotence in the face of globalization. Consequently, Crisis exteriorizes the fact that in the northern melting pot there is suspicion toward Latin-American culture, which is completely op-posed to the Anglo-American style. Crisis suggests that Americans only conceive Hispanic integration through a process of “Americanization” and “Dehispanization”, even if that means playing the part of the migrant hunters or becoming cannon fodder for the US Army. In fact, the allusion to the participation of Latino soldiers in the American military campaigns in the Middle East shed light on the incongruousness of a system that condemns Latin-American violence but naturalizes those undocumented migrants who accept to become mercenaries of the system.

Crisis demonstrates that economic decline is one of many aspects of a human decadence characterized by the elimination of idealistic heroism. Latin Americans have become a sort of derived products of the hegemonic order; they are part of a kind of liberal alchemy. Crisis suggests that the financial crisis hides an intellectual degeneration that leads to the complete loss of individuality, the lack of societal values and to a profound existential crisis. “Hispanos” are part of a system constituted by a submissive flock that performs its economic and social role. The proof of this is the fact there is no epic dimension in Crisis. The novel exposes the de-humanization of society and shows that the Latin American Odyssey in the “land of Uncle Sam” is led by the duality of a pragmatic system that, on the one hand, needs foreign employees to work in precarious, atypical, insecure, or unprotected work conditions and on the other hand, deprives them of their civil rights. There is no fairy-tale ending in Crisis. The American dream is only a chimera. Crisis destroys the image of the USA as a land of integration, work, and success. The novel relates a series of failures and deceptions that confirm that the USA is not the Promised Land of Latin-Americans. In sum, Crisis’s characters are, in a certain sense, archetypes of the Latin Americans condition in the global world. They are the victims of the hegemonic violence, although sometimes they are not keenly aware of it. In fact, Crisis is an existential portrait of the contemporary Latin American migrant. Jorge Majfud seeks to go beyond the literary dimension of the exodus, adapting this topic to the historical reality of the globalized world, in which the Latin American diaspora is taking place.

References

Adams, James Truslow. The epic of America. New Brunswick. Transaction Pu-blishers. 2012.

Anagnostou-Laoutides, Eva. The Trojan Exodus: The Initiation of a Nation. Iris. 19 (2002), pp. 1–49.

Bellos, David. The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventure of Les Misérables. New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017.

Chomsky, Noam. Year 501: The conquest continues. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2015.

Dahl, Robert A. A democratic paradox? Political Science Quarterly. 115.1 (2000) , pp. 35–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/2658032

Galeano, Eduardo. Las venas abiertas, siete años después (I). El Viejo Topo. 22 (1979), pp. 9–17.

García-Teresa, Alberto. Crisis. Revista Viento Sur. 1.26 (2013), pp. 127–128. Goldhamer, Herbert. The Foreign Powers in Latin America. Princeton. Prince-

ton University Press. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400869152

Hytrek, Gary. Introduction: globalization and social change in Latin Ame-rica. Latin American Perspective. 29.5 (2000), pp. 3–6. https://doi. org/10.1177/0094582X0202900501

Larsson, Göran. Bound for Freedom: The Book of Exodus in Jewish and Chris–tian Traditions. Peabody. Hendrickson. 1999.

Lee, Youngro. To dream or not to dream: A cost-benefit analysis of the De-velopment, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy. 16.1 (2006), pp. 232–261.

Majfud, Jorge. Crisis. Tenerife: El baile del sol. 2012.

Majfud, Jorge. La escritura sin anestesias de un uruguayo universal: Entrevista a Jorge Majfud por José Sarzi Amade y Leonor Taiano Campoverde. On-line: Revista Mito. 34 (2016): http://revistamito.com/la-escritura-sin-aneste-sias-de-un-uruguayo-universal-entrevista-a-jorge-majfud/

Mariscal, Jorge. Latino/as in the U. S. Military: Inside the Latino/a Experience: A Latino/a Studies Reader. New York. Palgrave/Macmillan. 2010, pp. 33–50.

Mattson, Kevin. Upton Sinclair and the other American century. Hoboken. Wiley. 2006.

Pérez Vega, David. Crisis, por Jorge Majfud. Desde la ciudad sin cines. 2014 http://desdelaciudadsincines.blogspot.com.es/2014/06/crisis-por-jorge-maj-fud.html

Taiano, Leonor. Huyendo hacia la paradoja del tío Sam: Consideraciones so-bre Crisis de Jorge Majfud. Finisterre: En el último lugar del mundo. Edi-ted by Wladimir Chávez & Leonor Taiano. México, Destiempos. 2017, pp. 123–148.

Trigo, Abril. 2016. Sobre las diversas maneras del migrar. Liminales. Escritos sobre psicología y sociedad. 1 (2016): 13–30. https://doi.org/10.54255/lim. vol1.num01.214

Tubbs, Michael. The Dictatorship of Capital. Salisbuty. Boolarong Press. 2013. Urzúa, Carlos M. Seis décadas de relaciones entre el Banco Mundial y México.

Estudios Empresariales. 2007, pp. 48–56.

Woo Morales, Ofelia. Abuso y violencia a las mujeres migrantes. Violencia contra la mujer en México. Edited by T. Fernández de Juan. México. Comi-sión Nacional de Derechos Humanos. 2004, pp. 71–84.

Wladimir Chávez, Leonor Taiano

& Gen Yamabe (eds.)

Finisterre II: Revisiting the Last Place on Earth

Migrations in Spanish and Latin American Culture and Literature.

Waxmann 2024

Münster • New York

Østfold University College (Norway)

[i] In fact, Crisis gives a retrospective view of the war through the three González: Tony Gonsález, Patrik Gonzáles and Robert González, these characters are the metaphor of the Latino presence in the American interventions

[ii] It is important to note that Crisis was written in 2012. At that time there were no governmental considerations about ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.