Alternate Variation of History

Although the Western representation of time continues to be a line where the future is forward and the past is backward, reality insists on proving older, more contemplative cultures right: the past is forward and the future is backward, which is why we can only see the former and not the latter. But predicting the future has been more important to humanity than finding the goose that lays the golden eggs.

In the work routine, for example, the most important element in any job application is the resume and the reference letters of the individual or the applying company. In any case, the section on projects and objectives is much smaller and less relevant than the rest, which refers to the applicant’s background, whether ethical or professional. Even though the employer is interested in what the candidate has to contribute in the future, when reading the resume and references, they always focus on analyzing the applicant’s past to form a vague idea of the future. Even artificial intelligence systems that read applications, whose goal is to predict a candidate’s behavior, do so exclusively based on their background.

On a larger scale, sociology and economics do the same: their main tools of understanding and prediction are not in equations but in history. This was already recognized by John Maynard Keynes when, after predicting the tragic consequences of the impositions on defeated Germany in World War I, he failed to foresee the great collapse of markets and economies in 1929. From his obsessive search for a pattern in the stock market, he came to recognize that the unpredictability of the economy is due to the “animal factor” of human psychology. Of course, he did not observe that the animal factor in humans is far more complex and unpredictable than in other animals.

Economists themselves have observed that even today, when one of them manages to predict a crisis, it is due to luck, not to any objective calculation. Out of hundreds and thousands of predictions made by economists before the great crisis of 2008, few specialists were correct. One of them was the economist Nouriel Roubini, who, after becoming famous for his prediction (which he attributed to his intuition, not to a mathematical calculation), continued making predictions that never materialized—even the nose can be wrong.

However, human history is not a succession of chaotic and disconnected events. It not only rhymes but also allows for the identification of certain common elements, certain patterns, such as the cyclical crises of capitalism described by Marx. It is also true that the search for patterns has its dangers, not because patterns do not exist (like the physical and psychological stages of human beings) but because their simplifications often lead to wrong and even opposite conclusions.

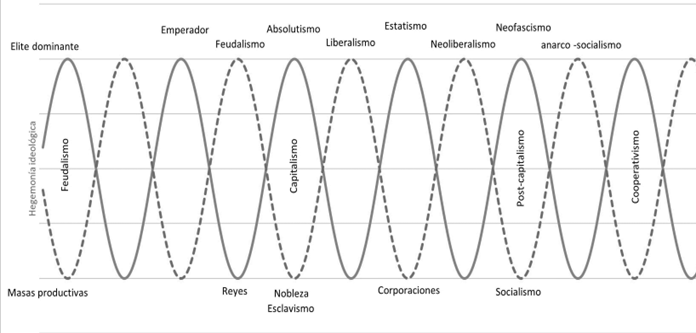

One of the simplest and most general abstractions derived from this study is a model we might call the inverse progression model.

(figure 1)

For reasons of space, for this model of history, we will limit ourselves to considering the last thousand years, analyzing only the last five centuries and focusing in more detail on our time. In this sense, we can observe that each period reacts against the previous one and crystallizes its demands, but, in all cases, it is a matter of opposing ideological narratives that serve the same goal: the accumulation of power in a dominant minority, usually the one percent of the population, through the exploitation of the rest by the exercise of physical coercion first, followed by narrative proselytism and, finally, consolidated by “common sense” and the obvious truths created by the media. Once the economic system convenient to the minority is exhausted by the growing inverse consensus of the majority (Christianity in the time of Constantine) or a new minority with growing power (the capitalist bourgeoisie of the 17th century), it is replaced by the alternative claimed by those below (movements against racism, sexism) and, finally, captured, hijacked, and colonized by the dominant minority. In this way, we can see a continuity between opposing ideologies, such as, for example, feudalism and liberalism, rural slavery and industrial corporatism, monarchical absolutism and Soviet statism.

We start from the axiom that the human condition is the result of a dialectic between a historical component and an ahistorical one that precedes it. We will focus mainly on the observation of the first element of the pair, history, but we will consider its ahistorical component as always present, as are psychic and physiological needs.

On the other hand, this model of reading history is based on another ahistorical component, denied for more than half a century by poststructuralist thought: the dualism of action and reaction in human action and perception. For example, in liberal democracies, elections are almost always decided by a coin toss, that is, by two or three percent of the votes. If not by one percent. In many other aspects of individual and social life, the complexity of reality is often reduced to a pair of opposites, from religions (good-evil, angel-demon, yin-yang), politics (right-left, state-private enterprise, socialism-capitalism, liberal-conservative, rich-poor) to any other aspect of intellectual and emotional life: up-down, white-black, forward-backward, cold-hot, pleasure-pain, inside-outside, euphoria-depression, etc.

In June 2016, in an interview about the possibilities of Donald Trump’s victory in the November elections, we mentioned this pattern and this emotional component in political elections, whereby if a goat were to compete with Mahatma Gandhi, after a certain period of electoral campaigning, the goat would close the supposed logical advantage of the rival candidate.[i] In June 2016, most polls and analysts dismissed a Trump victory. As in the 1844 elections, when everyone laughed at the intellectual shortcomings of candidate James Polk. In 2016, the difference in favor of Hillary Clinton was two percent of the total votes (though Trump was elected president due to the electoral college system inherited from the slaveholding era). In 1844, James Polk won the election by one percent, which ultimately led to a radical change in the history of the world in the following century.[1]

Capitalism emerges as a novelty and reaction (though neither intentional nor planned) against monarchical absolutism, which in turn had arisen as a reaction to feudalism and the power of the landowners. Its economic and ideological system opposes the feudal and absolutist systems while simultaneously drawing from both, and later, it ends up reproducing them with the consolidation of economic and financial corporations, through a radically different culture: the oligopolistic power of transnational corporations served by weaker neocolonial states and protected by central metropolises with almost absolute powers, expressions of democratic political systems indebted to dictatorial economic systems.

The new capitalist class, the bourgeoisie, founds and grounds its revolution in democratic opposition to kings and absolutism, but once it becomes the dominant class, spider-like, it does not abandon the tradition of minority accumulation over the majority. Since its banner is democracy, it cannot abandon it once power is monopolized, but must disguise it to continue the dynamic of appropriating the wealth-power of the majority. In this way, it was possible that throughout the Modern Age, the most brutal empires in the world were democracies. Its ideology, liberalism and more recently neoliberalism, also emerges as a critique of the power of the minority of its time (monarchical absolutism) and becomes the narrative that justifies the dominant power of the new minority, corporate and imperial, articulated by economists functional to the current power with a veneer of science and material objectivity. At the center of the new neoliberal narratives lies a purely ideological and cultural component: the reduction of human existence to a single goal: the pursuit of individual profit at any cost, even at the price of the most radical dehumanization, the simplification of the human being as a producing-consuming machine, and the destruction of the planet. All in the name of democracy and freedom.

Liberals are the continuation of feudal lords, opposed to absolutist kings (to central governments), but they cannot renounce the banner of freedom and democracy, even though they only have the words of these two principles, repeated mechanically like a rosary. By freedom, they mean the freedom of capitalist lords, of the minorities in financial power. By democracy, they mean that electoral system that can be bought every two or four years or, as Edward Bernays, the inventor of modern propaganda, will summarize, that system that tells people what to think for their own good.

In all cases, we will see a progressive divorce between narrative and reality until a new super crisis, a social and civilizational paradigm shift, causes both to collapse. The more words like freedom and democracy are hijacked and repeated, the less relevance they have. A reality creates a dominant narrative-web, and this narrative sustains the reality so that it does not dissolve in its own contradictions. To achieve this, the narrative resorts to religious sermonizing, in our time dominated by mass media.

In this study, we will analyze the most significant moments of the last four centuries of this dynamic. Based on the “Inverse Progression” proposal illustrated earlier, we will begin by projecting the same logic to earlier periods in the following scheme, which, without a doubt, must be adjusted in its details for greater clarity for different readers.

Scheme of Ideological Pairs

| Periods | Dominant | Resistant | ||

| Monocratic | Polycratic | Monocratic | Polycratic | |

| Antiquity | Polytheisms | Monotheisms | ||

| Classical Middle Ages | Empires | Tribes/Provinces | ||

| Confederation Republics Caliphates | Dictatorships Empires regional | |||

| Catholic Church | Non-canonical Christianities | |||

| Feudalism | Monarchy | |||

| Modern Era | Catholic Monarchy | Protestantism Liberalism | ||

| Liberalism Federalism | Monarchy Centralism | |||

| Imperialism | Anti-colonialism | |||

| Slavery Confederation | Nation, Union | |||

| 19th Century | Nation-Empire | Colonies | ||

| 20th Century | Corporate Capitalism | State Capitalism | ||

| Fascism Stalinism | Socialism Anarchism | |||

| Liberal Capitalism | State Socialism | |||

| State Capitalism | Social Democracies, Unionism | |||

| Neoliberalism Neofeudalism | Capitalist Socialism | |||

| 21st Century | Militarist Capitalism | Cooperative Democracy | ||

| Cooperative Democracy | Communist Capitalism | |||

Descriptive Examples

Before we begin, let’s provide a few brief examples. When capitalism emerged, feudalism simultaneously transformed into anti-monarchical liberalism in Europe and, later, into slavery against the central government in the United States. This ideocultural tradition persists today in the Southern principle of “defending state independence,” the same principle that led to the Civil War to maintain slavery over a century ago and later the transformation of slaveholders into CEOs and boards of dominant corporations.

Today, neoliberals repeat the imperial rhetoric of the free market when, in reality, they refer to the earlier school they refuted, mercantilism. Mercantilism was a system of currency accumulation that, to a large extent, practiced the interventionism of imperial states to protect their own economies and destroy those of their colonies through protectionist policies and forced purchases at gunpoint. Not without irony, the ideology of the capitalist free market ended the free market. What we have today, five centuries later, is corporate mercantilism, where corporations are no longer medieval guilds but the same feudal lords who accumulate more power than monarchies. Today, the surplus (capital accumulation) prescribed by the mercantilists of the past does not reside in national governments but in the neo-feudal lords of finance. Conversely, countries manage debts.

In the United States, as in other countries, the competition between two political parties will eventually lead to a role reversal, as with the Southern slaveholding Democrats and the Northern liberal Republicans in the past. The inverse identification of Southern Confederates with the Republican Party, to some extent starting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, or perhaps earlier during the Progressive Era, and of the leftist Democrats, follows this model and leads us to predict that it will eventually reverse again, especially given some demands of the Republican right that align with old demands of the Democratic left. I suspect this crossover and inflection will occur sooner in their disputes over international policy, which have never been very antagonistic. In chapters like “Social Networks Are Right-Wing,” we will provide a more recent case.

If we consider the immediate present and a projection into the future, we can see the case of the United States during Postcapitalism. Only in the last century, the superpower experienced the sine wave of the Inverse Progression in an accelerated manner, with periods of fifty years. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, progressive policies not only migrated from the Republicans to the Democrats but also established the paradigm for the next fifty years. This paradigm strengthened unions, made possible the creation of State Social Security, and allowed government intervention in the economy without major questioning. This cycle ended with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the triumph of the neoconservative-neoliberal reaction, also a consequence of the global crisis of the 1970s. In all cases, ideological changes were followed by transmutations and travesties of the elites at the top of the social power pyramid to maintain continuity amidst change.

Today, fifty years later, the system is once again in crisis for the third time, with minor symptoms but major causes. For the United States, it is not yet a massive economic crisis, but it is already a crisis of hegemony that will end its monetary privileges and, later, geopolitical ones. As happened with the crisis of the Spanish Empire in 1898, this country will have to turn to deep introspection.

This megacrisis will likely occur in the 2030s or 2040s, and it will be a new opportunity, judging by the dynamics of the Inverse Progression, for new generations to reorganize themselves into a system removed from neoliberalism, from capitalism as an existential framework, and to question the postcapitalist dictatorship with atomized options but with the common factor of a less consumerist and more cooperative politics and philosophy. The death of the capitalist paradigm will not mean the automatic disappearance of its institutions, but rather a new way of seeing and living in the world. Extending the theory of the Inverse Progression, it would not be an exaggeration to predict that, even if the two-party system remains, the current Republican Party, hijacked by the nationalist far-right, could even switch roles again in a few decades and represent these new aspirations that in the past century were associated with the left, while the Democratic Party would return to its 19th-century role of representing the conservative, corporate, and Eurocentric South. But this last point would be a detail.

In the 21st century, another pair begins to invert: a large number of center-left politicians and governments position themselves in favor of the “free market” and trade agreements (which have little to nothing to do with a free market but rather guarantee, in secret agreements like the TPP, the freedom of investors) while other conservative right-wing governments, such as that of Donald Trump, align with the traditional protectionist line of the left. While in the West the neo-feudal model represented by mega-companies and corporations whose powers surpass those of the states signifies not only the death of classical capitalism but also a return to its socioeconomic predecessor, feudalism, in China the system of state capitalism centered on the Communist Party is a confirmation of the monarchical model, where the fiefdoms (the corporations) are subordinated to the State.

Corollary

In a Cartesian graph we can place on the x-axis a progression ranging from (a) absolute government (x=0) to (z) absolute and self-regulated anarchy (x=10) and on the y-axis we distribute the degree of religious fanaticism, starting from (a’) a radically secular or atheist society (y=0) to another (z’) theocratic or sectarian society (y=10). We could speculate that in secular societies with centralized governments, like China, their position would be: x→0; y→0. The Middle Ages or Feudal period could be placed at the top of the curve (x→5; y→10) with a fragmented political power, that of the feudal lords, but not anarchic-democratic. The extreme x→10; y→0 signifies a break with the Middle Ages where the fragmentation of power has surpassed the maximum curve of religious sectarianism to render it ineffective as a ligament (religion, re-ligare) of the concentrated and independent powers of the feudal lords of the Middle Ages or the financial elites of our time. Obviously, the crossing of this critical point (x→5; y→10) cannot occur without a general upheaval, a conflict likely on a global scale.

(figure 2)

[1] We explained this in The Wild Frontier (2021).

[i] Radio Uruguay. (2016). “La teoría de la cabra de Majfud”. 14 de junio de 2016: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1DXbl2MvIA

From Flies in the Spiderweb: History of the Commercialization of Existence—and Its Means, by Jorge Majfud

Majfud, Jorge. Flies in the Spiderweb: History of the Commercialization of Existence—and Its Means. Humanus, 2023, 2025, p. 17-25

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.