Como millones de personas alrededor del mundo, he mantenido admiración y respeto por Noam Chomsky desde mis años de la secundaria y, más tarde, agradecimiento por un constante intercambio y colaboración en los quince años previos a su colapso de salud. Lo mismo puedo decir de su hija, la brillante historiadora y amiga Aviva Chomsky.

Si, por un lado, considero su amistad o relación con Jeffrey Epstein una dolorosa falta de juicio, por el otro, me parece brutalmente injusta la liviandad de muchas acusaciones y ataques de amnesia que ha sido objeto por los emails y las fotos con Epstein y con Ehud Barak en un salón de clase, que los medios han reproducido durante el año 2025. Esos mismos que, por pudor y obediencia, nunca han usado la palabra genocidio para referirse a Gaza o imperialismo para el acoso descarado a Venezuela.

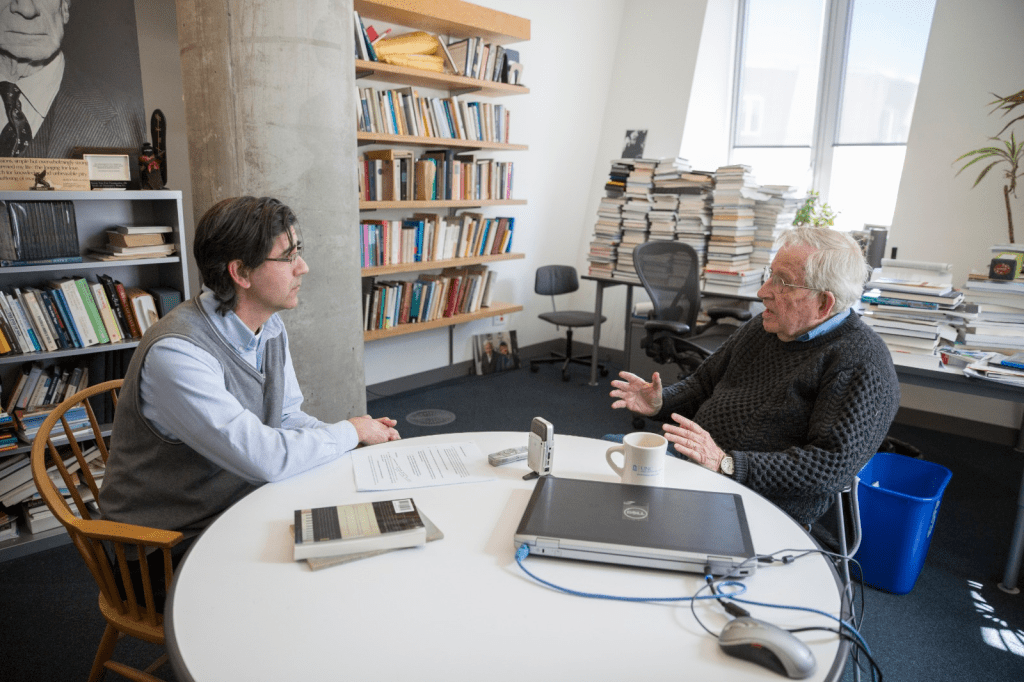

Años atrás, Noam respondió a mi reclamo de explicaciones: “siempre estuvimos a favor de una segunda oportunidad para los exconvictos…” me escribió en una extensa carta. Luego: cualquier contacto entre ambos “fue totalmente público, algo por lo que los medios nunca se interesaron, excepto ahora; nunca se interesaron porque, por entonces, no había nada que ocultar […] Hasta las serias revelaciones de 2019, él tenía una vida pública con muchos científicos de Cambridge”. En otro momento: “Imposible saber lo que luego se reveló […] Tanto el WSJ como otros medios siempre han tenido en su agenda una campaña de difamación contra mí”. En otro intercambio, Noam me refirió al titulado “movimiento bancario” que hizo a través de un tercero con una cuenta de su esposa fallecida para cancelar la deuda que tenía por su prolongada enfermedad. Por respeto, no seré yo quien revele detalles personales de un amigo.

Aunque me encerré en la incredulidad, nunca pude aceptar ese último capítulo (epílogo) de Noam, más allá de sus casi 90 años. Aquellos escritores y profesores que, por no ser tan importantes, nunca caímos en ese tipo de relaciones inoculadas, la tuvimos más fácil (más allá de que, caminando por el campus de la universidad o en la oficina, estudiantes o visitantes nos piden con frecuencia alguna fotografía que no rechazamos para no pasar por arrogantes), por lo que quisiera volver a los ataques de amnesia a los que me refería al comienzo.

Ahora, no pocos desde la izquierda practican el clásico sacrificio en el altar del ídolo, el deseado apuñalamiento del padre, en términos psicoanalíticos. De paso, se materializa el objetivo de la CIA y del Mossad de desacreditar todo su trabajo y su lucha anterior y, sobre todo, de (intentar) desmoralizar a muchos de quienes quedan en la misma trinchera de luchas contra el imperialismo, las sectas y las agencias secretas que siguen gobernando el mundo.

La excelente periodista Irene Zugasti, escribió sobre Chomsky: “Tiendo, quizá de forma reactiva no sé, a alejarme cada vez más de cualquier intelectualidad progresista que salga de EEUU”. Sólo la cito como un caso entre muchos. Una lectora de América Latina me envió la siguiente respuesta: “Casualidad, yo tiendo, quizá de forma reactiva no sé, a alejarme cada vez más de cualquier intelectualidad progresista que salga de la Corona Española”. Ambas expresiones son sectarias, nacionalistas, autoindulgentes, llenas de prejuicios y de poca memoria, pero la segunda es una observación crítica y sarcástica.

Respeto el trabajo que hacen desde su programa de televisión en España, La Base, pero convengamos que tampoco tiene nada de heroico. Su conductor, el fundador de Podemos y exministro Pablo Iglesias, aunque un analista y comunicador de gran valor, no es el ejemplo y modelo de la izquierda mundial, no solo porque es imperfecto como cualquier hombre (más quienes hacen algo), sino porque no hay dos personas en el mundo que piensen exactamente lo mismo.

Es amnesia súbita juzgar a un individuo y a toda una historia heroica de estadounidenses, olvidando los Martin Luther King, los Malcolm X y los Fred Hampton. Incluso, olvidando aquellos desde posiciones donde no estaban en juego sus vidas, pero sí sus trabajos, su vida civil, y la estabilidad de sus familias, como Harriet Beecher Stowe, Victoria Woodhull, Mark Twain, Orson Welles, Noam Chomsky, Arthur Miller, Edward Said, Nina Simone, Mohammed Ali, Edward Snowden o Norman Finkelstein.

Cuando muchos de nosotros no habíamos nacido, Chomsky era arrestado frente al Pentágono por sus clases abiertas contra la guerra de Vietnam y se enfrentaba en los medios y en los atriles contra imperialistas y sionistas supremacistas en los tiempos más difíciles, como ninguno de sus ahora enterradores de izquierda lo hizo nunca.

De hecho, el mismo año que Irene Zugasti nació (1988), Chomsky publicaba una de sus obras maestras, la que influyó en millones de lectores y activistas alrededor del mundo, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media; se enfrentaba en la Universidad de Ohio al asesor de defensa de Ronald Reagan, Richard Perle; visitaba los Territorios ocupados de Palestina (Israel le prohibirá volver) como lo hizo su amigo, el célebre profesor palestino de la Universidad de Columbia, Edward Said; y en el Líbano daba una conferencia crítica contra el imperialismo y el apartheid israelí. El año en que yo nací (1969), Chomsky dio la conferencia “Paz en el Medio Oriente” sobre la necesidad de crear en Palestina un Estado único y secular con igualdad legal, más allá de religiones y etnias, en lugar de un Estado gobernado por una de las partes o de dos Estados separados…

Ese era y es el objetivo de agentes del Mossad como Jeffry Epstein: la muerte civil de símbolos antimperialistas y la extorsión de políticos imperiales, con los cuales se pueda controlar la narrativa, la trasferencia de capitales y tecnología, y se puedan decidir guerras y aceptar masacres de pueblos incómodos como algo normal, necesario y justo.

En el pasado se practicó ese mismo recurso de la extorsión por razones de alcoba a políticos tan diversos como John Kennedy y Juan Domingo Perón. Lo mismo hizo el FBI con el doctor Martin Luther King (otro hombre con debilidades por las mujeres), a quien se lo quiso extorsionar con sus relaciones extramaritales con la esperanza de que volviese a caer en su depresión de adolescente e intentase, una vez más, quitarse la vida para ahorrarse lo que luego resultó la única solución. Lo mismo hizo el FBI con John Lennon, a quien quiso extorsionar con un archivo sobre una homosexualidad que no solo no le encontraron, sino que, para mal de extorsionadores, luego dejó de significar muerte civil debido al activismo por los derechos a la diversidad sexual que convirtieron un pecado mortal en un orgullo. Así que sólo les quedó lo que nadie podía defender, ni por izquierda ni por derecha: el abuso de menores, el crimen más repugnante de los cuales los poderosos suelen ser autores impunes, siempre y cuando permanezcan en estado de obediencia.

Hoy le diría a Chomsky, “te equivocaste feo”, “a la basura hay que mantenerla lejos”, y algún otro lugar común. No voy a defenderlo en esto, pero tampoco me sumaré a la cobardía de quienes hoy se creen moralmente superiores cuando se ha establecido una nueva resistencia masiva y se olvidan de quién abrió caminos en la vanguardia de una guerra brutal a lo largo de tres generaciones, cuando nosotros no habíamos nacido aún o, todavía en la secundaria, aceptábamos más de un cliché parasitario del poder que, gracias a unos pocos como Chomsky, terminamos por extirpar de nuestras jóvenes consciencias.

En mayo de 2023, poco antes de su ictus, Noam cerraba un correo que me envió con un comentario sarcástico sobre un periodista: “Cuando no pueden responder a alguien que odian, la calumnia es siempre una opción”.

Jorge Majfud, diciembre 2025

https://www.pagina12.com.ar/2025/12/22/tiren-contra-chomsky/

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.