Alexandere H. Hunter

2025

© Alexandere H. Hunter 2025

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without express written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Please refer all pertinent questions to the publisher.

Abstract

This thesis examines Jorge Majfud’s The Wild Frontier: 200 Years of Anglo-Saxon Fanaticism in Latin America as a philosophical and historical critique of the moral foundations of Modern Western civilization. Drawing from theoretical frameworks rooted in postcolonial, decolonial, and critical theory, it explores Majfud’s concept of the ‘frontier’ as a moral and ideological construction. The study situates Majfud in dialogue with thinkers such as Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, Michel Foucault, Hannah Arendt, and José Martí, revealing how the frontier myth serves as both a geographic and psychological boundary that legitimizes domination and exclusion. Through interpretive methodology, this research traces the continuity of imperial ideology from the colonial era to contemporary global capitalism. Ultimately, the thesis argues that Majfud’s work provides a unique synthesis of critical theory and ethical humanism, offering a moral framework to understand and transcend the violence embedded in Western modernity.

Table of Contents

Religion, Morality, and Empire. 18

Colonial Violence and Economic Expansion. 19

Banana Wars and the new Era of protectorates. 45

An Era of psychological warfare and media manipulation. 53

The role of the CIA: the pen and the sword. 63

A project for the New American Century. 71

Intellectual and Philosophical Contexts. 89

Majfud and Related Thinkers. 97

Synthesis: Majfud’s Place in Critical Thought 100

Conclusion: The Frontier as a Moral Framework. 102

Introduction

Jorge Majfud’s The Wild Frontier: 200 Years of Anglo-Saxon Fanaticism in Latin America represents a profound philosophical inquiry into the moral architecture of Western civilization. This thesis seeks to interpret Majfud’s work as a sustained critique of the ideological mechanisms that have defined and justified imperial expansion, racial hierarchies, and the myth of progress. Through historical and textual analysis, this research examines the frontier not merely as a territorial boundary but as a cultural and psychological construct that organizes Western identity around violence, faith, and self-justification. The study explores how these myths have evolved from the early colonial conquests to modern globalization, sustaining a moral duality that allows domination to be recast as virtue.

Theoretical Framework

This study situates Majfud’s work within a constellation of critical thinkers who have examined the intersection of power, knowledge, and morality. It draws on Frantz Fanon’s notion of colonial violence, Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism, Michel Foucault’s genealogy of power, and Walter Mignolo’s decolonial critique of modernity. Majfud extends these discourses by integrating them into a moral and literary framework, emphasizing the ethical dimensions of historical violence. His synthesis of philosophy, history, and literature positions him at the crossroads of critical theory and humanist ethics. This theoretical foundation allows for an interpretation of the ‘frontier’ as both an epistemological and psychological boundary that defines who is human and who is expendable.

Methodology

The methodology adopted in this thesis is interpretive and hermeneutical, grounded in philosophical analysis rather than empirical observation. The research involves a close reading of The Wild Frontier and related writings by Majfud, contextualized within broader intellectual traditions. The approach follows a genealogical method inspired by Foucault, tracing the historical evolution of the frontier myth as a discourse of power. It also applies a moral hermeneutic framework, seeking to uncover the ethical implications of ideological narratives. Comparative analysis is used to place Majfud in dialogue with other critical thinkers, allowing the synthesis of diverse intellectual traditions into a coherent interpretive model.

Analysis

Majfud’s central argument is that the Western concept of the frontier is not merely geographical but metaphysical―a moral line dividing civilization from barbarism, self from other. This line has historically justified conquest and violence while sustaining the illusion of progress. The frontier myth, originating in Puritan theology and colonial ideology, transforms domination into divine mission. From the extermination of Indigenous peoples to modern imperial interventions, Majfud demonstrates that the logic of the frontier persists under changing forms: religious salvation, economic development, and national security. His work exposes how this logic creates a self-reinforcing moral blindness that sanctifies aggression as defense and exploitation as freedom.

Comparative Discussion

Majfud’s analysis resonates deeply with Fanon’s concept of colonial alienation and Said’s critique of Western representation. Like Fanon, Majfud perceives violence as the constitutive act of Western civilization; like Said, he identifies the production of the ‘Other’ as central to imperial identity. However, Majfud introduces a distinct ethical dimension by merging structural critique with moral reflection. His work recalls Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil, showing how ordinary citizens become participants in systemic violence through ideological faith. In conversation with decolonial thinkers such as Mignolo and Dussel, Majfud broadens the critique of modernity to include psychological and spiritual complicity, proposing that true decolonization requires moral awareness.

Introduction

Jorge Majfud’s The Wild Frontier: 200 Years of Anglo-Saxon Fanaticism in Latin America offers a far-reaching historical and philosophical investigation into the entanglement of violence, ideology, and power in shaping Western identity—particularly that of the United States and Latin America. Through the notion of the “wild frontier,” Majfud interrogates the symbolic and material boundaries that have defined the dichotomies of civilization and barbarism, progress and destruction, self and other. The “frontier,” he argues, functions not merely as a territorial limit but as a moral and cultural paradigm that has historically justified conquest, slavery, and imperial expansion under the guise of liberty, democracy, and divine purpose.

Drawing upon historical evidence, political critique, and literary reflection, Majfud revisits critical junctures—from the European colonization of the Americas and the genocide of Indigenous peoples to the ideological battles of globalization—to reveal the enduring logic of domination beneath shifting political languages. At the same time, he foregrounds the voices of resistance that challenge these hegemonic narratives, exposing the ethical contradictions embedded within the “civilizing mission.”

Ultimately, The Wild Frontier functions as both a historical critique and a philosophical meditation on the persistence of violence masked as virtue. Majfud’s prose oscillates between analytical precision and lyrical reflection, offering an interdisciplinary synthesis of history, philosophy, and literary insight. His work dismantles the comforting myths of Western exceptionalism, situating modern civilization within a genealogy of conquest, self-deception, and moral blindness.

Analysis

Majfud’s central thesis situates the frontier as a multidimensional construct—geographical, cultural, religious, and psychological—that continues to shape Western consciousness. The frontier, he contends, is the locus where moral justification and material expansion intersect, legitimizing domination through narratives of faith, reason, and progress. The following sections examine the major thematic axes of his argument.

The Myth of the Frontier

Majfud begins by revisiting the mythological status of the frontier in U.S. historiography, from the Puritans’ settler ethos to Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis.” He deconstructs the popular notion that the frontier fostered democracy and individualism, revealing instead a history of extermination, enslavement, and ideological rationalization of expansion. For Majfud, the frontier is less a space of liberation than a theater of conquest in which violence becomes a civic virtue and moral imperative.

Religion, Morality, and Empire

A crucial dimension of Majfud’s analysis lies in his treatment of religious discourse as a legitimizing force for empire. The Puritan notion of a “New Israel” endowed colonial expansion with divine sanction, transforming conquest into a sacred duty. Majfud identifies this theological rhetoric as the precursor to American exceptionalism—a narrative through which moral certainty conceals systemic violence. The fusion of faith and politics, he argues, produced a cultural self-image incapable of recognizing its own brutality.

The Frontier Within

Moving from geography to psychology, Majfud theorizes the frontier as an internal phenomenon—a symbolic struggle between the civilized and the wild, the rational and the emotional. This inner frontier perpetuates moral dualisms such as good versus evil or order versus chaos. The repression of the “wild” elements of the self—often gendered, emotional, or foreign—projects otherness onto colonized peoples, providing ideological justification for their subjugation.

Colonial Violence and Economic Expansion

Majfud links economic exploitation to the ideological discourse of civilization. European imperialism, he argues, cloaked commercial and territorial ambitions in moral and religious rhetoric. The industrialization of slavery, the fabrication of racial hierarchies, and the myth of “progress” all served to naturalize systemic exploitation. This colonial logic persists in contemporary capitalism, where global inequality continues to reproduce the same moral justifications under new economic terms.

The American Century

The twentieth century, for Majfud, represents the global extension of the frontier mentality. U.S. interventions in Latin America, the Cold War, and the Middle East illustrate how the defense of “freedom” repeatedly translates into campaigns of domination. Majfud analyzes the role of media, consumerism, and technology in constructing a moralized imperialism—one that operates through persuasion and representation rather than overt conquest but remains equally violent in its effects.

The Frontier Today

In contemporary contexts, Majfud identifies new manifestations of the frontier: the digital frontier of surveillance and data control, the economic frontier of global inequality, and the moral frontier separating “civilized nations” from “failed states.” Though the rhetoric has evolved—invoking democracy, security, or markets—the logic of domination persists. Majfud calls for dismantling these moral illusions through critical self-awareness and compassion, proposing that the true frontier lies within human consciousness rather than between nations.

Original Spanish cover of the first 2021 edition

By land, by sea, by air

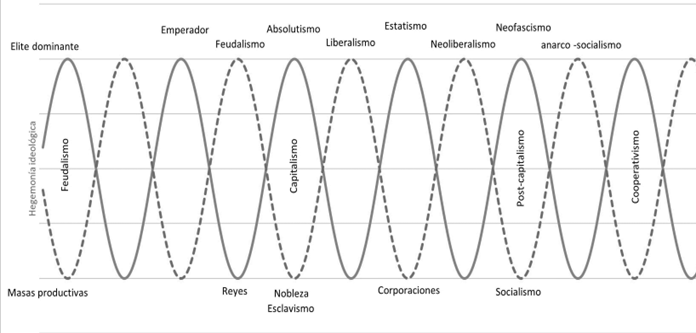

The Wild Frontier is not a chronological history but a moral cartography of imperial power. Divided into three great movements—By Land, By Sea, and By Air—the book traces how the United States transformed its expansionist mission from the physical conquest of territories to the ideological and psychological domination of entire nations. Each stage marks an evolution in the methods of control, yet the underlying logic remains constant: the pursuit of power through a fanatical belief in divine exceptionalism and racial superiority. The frontier, for Majfud, is not merely a line on a map but a state of mind—a moral boundary that continually expands under new disguises.

By Land begins with the birth of the United States and the conquest of its first frontier: the continent itself. It is the story of expansion through rifles and treaties, through settlers who called themselves victims while annihilating Indigenous nations. Majfud reconstructs this history through letters, speeches, and confessions that reveal how every invasion was justified as self-defense. The extermination of Native Americans, the annexation of half of Mexico, and the institution of slavery were all acts of “liberation” in the language of the victors. Andrew Jackson, Stephen Austin, and John C. Calhoun appear not only as political figures but as prophets of a new faith—the faith that violence, when baptized by the word “freedom,” becomes virtue. In these pages, Majfud unearths the mythology that made possible the transformation of genocide into destiny. The land was not merely conquered; it was rewritten. To possess the continent was to invent a new kind of truth: that the aggressor is always the defender, and that liberty belongs only to those who already possess power.

By Sea follows the empire’s expansion beyond its continental borders. When the land was no longer enough, the ocean became the next frontier. Here Majfud shows how the same logic of domination, once applied to the plains and deserts, migrated to the Caribbean, Central America, and the Pacific. The age of gunboats replaced the age of pioneers, but the language remained the same. The Spanish-American War, the occupations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the installation of protectorates in Cuba and Panama—all were carried out under the banner of civilization. The rhetoric of “liberation” concealed the raw mechanics of corporate capitalism. The Marine Corps became the army of United Fruit, Standard Oil, and National City Bank. Through these case studies, Majfud paints a vivid portrait of how private companies and public institutions merged into a single imperial organism. In this maritime phase, the frontier ceases to be geographic and becomes economic; the sea connects not just lands but markets. The ocean is freedom’s new metaphor, yet its waters are filled with corpses. “The flag follows the dollar,” Majfud writes, “and the soldiers follow the flag.”

By Air represents the culmination of this process, where physical occupation gives way to psychological and technological domination. After World War II, the empire no longer needed to seize land or ports; it needed to control minds. The frontier now floats in the invisible space of ideology, information, and fear. The CIA emerges as the new conquistador, replacing armies with agents, and cannons with communication networks. Airplanes bombed not only cities but imaginations. Propaganda became a weapon as powerful as napalm. Majfud recounts the coups in Guatemala, Brazil, and Chile, not as isolated political events but as expressions of a broader transformation: the empire of land and sea had evolved into an empire of air—weightless, invisible, omnipresent. He shows how Operation Condor, the network of dictatorships coordinated under Washington’s supervision, turned the southern hemisphere into an experimental field for the politics of terror. Through radio, television, and later digital media, the imperial narrative reached everywhere, teaching entire populations to see their own suffering as a necessary sacrifice for “freedom.” The air frontier is, in essence, the conquest of perception itself.

Majfud structures his book this way not for stylistic convenience but to reveal a deep historical pattern. Each frontier—land, sea, air—represents a stage in the sophistication of domination. The instruments change, but the psychology remains. The first frontier kills bodies, the second enslaves economies, and the third colonizes consciousness. Together they form a complete system of control, rooted in the same moral contradiction that has haunted the United States since its birth: the simultaneous worship of liberty and submission to empire. The book’s architecture mirrors the evolution of imperial technology—from muskets to markets to media—while exposing the unbroken continuity of the ideology that justifies them.

Yet Majfud’s purpose is not only to denounce; it is to diagnose. By understanding these frontiers as interconnected phases of the same historical disease, he invites readers to see beyond the surface of political events and into the anatomy of power itself. The savage frontier, he suggests, is not the wilderness that lies beyond civilization—it is civilization’s own shadow. The violence that once operated through the body now operates through the image. The invasion no longer begins with armies crossing borders but with words crossing screens. And still, as in the 19th century, the invader calls himself the victim.

In the end, The Wild Frontier is a meditation on the persistence of empire under the illusion of progress. “By Land,” “By Sea,” and “By Air” are not just historical divisions but moral allegories of how power reinvents itself to survive. From the rifles of Texas to the drones of the Middle East, from the plantation to the multinational corporation, from the cross to the corporate logo, the same logic continues to breathe: the belief that domination is destiny and that God, or freedom, or democracy will always bless the conqueror. Majfud’s brilliance lies in exposing the continuity beneath the change—the same frontier endlessly reborn, moving from soil to sea to sky, until it reaches the most intimate territory of all: the human mind.

God, race, and guns

Majfud unravels one of the most revealing contradictions in the history of the United States: the same racist ideology that justified the conquest of half of Mexico also forced the conquerors to stop at the Rio Grande. The logic of domination that drove the expansion of slavery, the extermination of Indigenous nations, and the annexation of territories met its own limit—not in morality or resistance, but in fear of racial contamination. The war against Mexico, which Majfud presents as both a continuation and a mutation of the ideology of slavery, exposes the dark heart of Manifest Destiny: a project that claimed divine sanction to spread freedom while depending on the enslavement of others to sustain itself.

The expansion of slavery was not a regional anomaly or a moral misstep, but the economic and spiritual engine of the American nation in the 19th century. From Virginia to Texas, slavery was the foundation upon which the “empire of liberty” was built. The southern elite saw no contradiction between the Declaration of Independence and human bondage, because liberty, in their language, meant the liberty to own, exploit, and conquer. For them, freedom was not a universal right but a privilege of race. Majfud shows how this perverse logic made the invasion of Mexico inevitable. Texas, wrested from Mexican sovereignty in 1836, was the first experiment in a larger design to expand the “peculiar institution” westward and southward. The Mexican Republic, which had abolished slavery in 1829, was therefore not merely a neighboring nation—it was an ideological affront. Its very existence challenged the racial and theological foundations of the United States. The war that followed, beginning in 1846, was not fought for security or self-defense, as American politicians claimed, but to restore the balance of a racial order that could not tolerate a free, mixed, and Catholic neighbor.

Majfud resurrects the voices of that era—letters from soldiers, speeches in Congress, and editorials from the American press—to reveal the psychological machinery of the conquest. The invaders declared themselves the invaded, insisting that Mexico had attacked first. They spoke of civilization triumphing over barbarism, of God’s will guiding them to spread democracy, while privately admitting, as Senator John C. Calhoun did, that the real issue was racial. “We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race,” Calhoun told Congress. “The great misfortunes of Spanish America are due to the fatal error of placing colored races on an equality with the white race.” It was not greed that stopped the conquerors at the gates of Mexico City; it was terror—the terror of inclusion, of diluting the purity of the white republic. The American army could take all of Mexico, but the American imagination could not absorb it.

The Rio Grande thus became more than a border; it became a moral quarantine. The same ideology that demanded expansion also demanded exclusion. The Anglo-Saxon republic needed new lands to exploit, but only if those lands could be emptied of people or filled with slaves. Once conquest threatened to merge with equality, it ceased to be desirable. Majfud notes that after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States possessed the means to annex all of Mexico but refused. Not because of fatigue or diplomacy, but because absorbing millions of mestizos and Indians would violate the racial architecture of the nation. The idea of freedom, built on exclusion, could not survive contact with the Other. The war achieved its goal—to seize the richest territories and reestablish slavery where it had been abolished—but it also revealed the fragile psychological limits of the empire.

This same fear later defined Washington’s attitude toward the Caribbean and Central America. After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the economic model changed, but the racial logic persisted. The Caribbean islands, with their Black and mixed populations, and the Central American republics, ruled by Indigenous and mestizo majorities, were seen as too dark, too impure, too foreign to be part of the “nation of the free.” Instead of annexation, Washington developed a new system: domination without absorption. Protectorates, puppet governments, and corporate empires replaced territorial expansion. The banana republics were the logical continuation of the slave plantations—still exploited, still subordinate, but kept safely at a racial distance. The empire learned to project power without contamination.

Majfud interprets this historical transition not as progress, but as a mutation of the same disease. The frontier shifted from physical to ideological space, but the underlying fear remained: the fear of equality. The very word “union,” sacred in American political mythology, was racialized from its inception. To keep the union pure, the conquered had to remain outside. This is why, in the 20th century, even as Washington preached democracy, it supported white oligarchies and dictatorships in Latin America; they preserved the racial hierarchy that annexation would have destroyed. The empire’s moral order depended on separation—on maintaining the illusion that freedom could coexist with domination as long as the dominated remained invisible.

Majfud’s insight into this contradiction is devastating. The same racism that justified conquest also set its boundaries. Expansion was never an expression of strength alone; it was an expression of fear disguised as destiny. The frontier could expand only so far before it touched what the empire most dreaded: the humanity of the conquered. In that sense, the border was not drawn by geography or diplomacy, but by the psychology of supremacy. The Rio Grande, the Caribbean Sea, and the invisible lines of modern foreign policy all trace the same circle of exclusion, the same anxiety that built a “nation for the Caucasian race” and called it the land of the free.

For Majfud, the tragedy of this history lies in its continuity. The empire that once stopped at the Rio Grande continues to patrol its new frontiers—not to prevent invasion, but to preserve illusion. The language has changed, the enemies have changed, but the logic endures. What was once the fear of the Black or the Indian is now the fear of the immigrant, the socialist, the Other who reminds the empire of its origins. The frontier remains savage not because of those who live beyond it, but because of those who built it. In the end, Majfud’s history is not about borders between nations, but about the borders within the human heart—where freedom and domination, love and fear, are still fighting the same war.

We were attacked first

One of the most enduring psychological pillars of Anglo-American expansion is the myth of self-victimization. From the earliest Puritan settlements to the modern CIA interventions, the aggressor has spoken the language of the threatened, the conqueror has worn the mask of the invaded. The United States, Majfud argues, was not only built through conquest but through narrative control—the ability to turn every act of aggression into an act of defense. This “sacred right to self-defense” became the moral foundation of empire, the formula that justified everything from genocide to preemptive war.

Majfud opens his chronicle with the earliest treaties between white settlers and Native nations, agreements conceived not as peace offerings but as instruments of deception. Every treaty was temporary, designed to be broken as soon as the settlers grew strong enough to expand. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson, came after decades of solemn promises to respect Native sovereignty. The Cherokee, the Choctaw, and the Creek had all signed treaties recognizing their lands as independent territories. Yet when gold was discovered or cotton required more soil, the agreements were erased by a familiar justification: “they attacked us first.” Reports of fabricated ambushes, staged provocations, or exaggerated threats appeared in newspapers and official correspondence to legitimize the next round of expulsions. Majfud notes that this rhetorical pattern—declaring innocence while committing violence—was not an accident but the founding grammar of a national identity built on conquest.

The Trail of Tears, where thousands of Indigenous men, women, and children were forced to march westward under brutal conditions, was defended in Congress as a humanitarian act, a necessary removal to protect both sides from “inevitable conflict.” Jackson himself insisted that the measure would prevent bloodshed, reversing the roles of killer and victim. The violence of the state was presented as an act of mercy. In this moral inversion, the victim’s resistance became aggression, and the conqueror’s expansion became peacekeeping. “Every massacre was a defense of liberty,” Majfud writes, “and every broken treaty a new promise of civilization.”

The same script repeated itself on the Mexican border. In 1836, when American settlers in Texas—many of them slaveholders—rebelled against the Mexican Republic, they claimed that Mexico had violated their rights and persecuted them for their religion and freedom. In truth, as Majfud reminds us, Mexico had simply enforced its abolition of slavery. Yet within a few years, the rebellion was celebrated as the triumph of freedom over tyranny. When the U.S. Army invaded Mexico in 1846, President James K. Polk announced to Congress that “American blood has been shed upon American soil,” a deliberate falsehood meant to provoke patriotic outrage. The skirmish that served as the pretext for war had occurred on disputed land that Mexico never ceded. The pattern was identical to the broken Indian treaties: invent an offense, claim the moral high ground, and let righteousness conceal greed. The result was the annexation of half of Mexico, baptized not as theft but as destiny.

Majfud lingers on the irony that the same politicians who justified the war in moral terms often admitted their motives in private. Senator Lewis Cass confessed that the United States had no intention of incorporating Mexico’s people, only its land. John C. Calhoun warned that annexing a “mongrel race” would corrupt the purity of the republic. They wanted territory, not Mexicans—resources without responsibility. The doctrine of self-defense provided the perfect alibi: they could take everything and still believe themselves innocent. “It is the genius of American imperialism,” Majfud writes, “to kill with one hand and pray with the other.”

The cycle continued into the twentieth century, where the moral vocabulary of self-defense evolved into that of humanitarian intervention. The occupation of Cuba in 1898, the invasion of Nicaragua in 1912, and the repeated landings of Marines in Haiti and the Dominican Republic were all justified as responses to disorder, instability, or threats to American citizens abroad. The sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor—likely an accident—became the rallying cry “Remember the Maine,” the false flag that transformed public opinion and ignited the Spanish-American War. Once again, the empire declared itself under attack, acting not as invader but as protector. In Majfud’s account, this event marks the industrialization of the old frontier myth: the mass production of self-victimization through media. The press no longer reported lies; it manufactured them.

During the Cold War, the same pattern reappeared with new technology and a new enemy. Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973, and countless covert operations across Latin America were all executed under the banner of defense—defense against communism, against instability, against chaos. Majfud shows how the CIA perfected the logic of the false flag, orchestrating coups and assassinations while claiming to preserve democracy. The illusion of danger replaced the need for actual threat. The empire no longer needed Mexico or the Sioux to shoot first; it could invent the shot itself. What had begun as a frontier myth evolved into a global ideology: the permanent right to act in self-defense, even when no attack existed.

At the core of this long tradition, Majfud identifies a theological impulse. The American empire inherited from its Puritan ancestors the belief that suffering is a sign of virtue. To be attacked—or to believe one is attacked—confers moral superiority. Thus, each war, each invasion, each coup d’état could be sanctified as an act of reluctant righteousness. The aggressor becomes the martyr, the destroyer becomes the savior. This self-image, Majfud argues, is more dangerous than weapons, because it transforms violence into faith. “A myth,” he writes, “is stronger than an army, because it fights inside us.”

The broken treaties, the false flags, and the permanent claim to self-defense are not isolated episodes but variations of a single melody. The United States, born from a rebellion against empire, recreated the very empire it once denounced, sustained by the same logic of divine exception. From the Cherokee lands to Baghdad, from the Rio Grande to the Caribbean, the justification remains unchanged: we were attacked, therefore we must defend ourselves. Majfud concludes that this is the true genius of the American narrative—not the power to conquer, but the power to feel innocent while conquering.

In the end, The Wild Frontier leaves us with a haunting truth. The history of empire is not a sequence of wars and treaties, but a series of stories—stories in which the most powerful nation on earth convinces itself, again and again, that it is the victim. To recognize this inversion is to see the empire for what it truly is: not a defender of freedom, but the author of its own perpetual attack. Only when that myth collapses, Majfud suggests, can peace become more than another broken promise.

Banana Wars and the new Era of protectorates

One of the most grotesque chapters of modern imperial history is the creation of the “Banana Republics.” Behind the euphemistic term lies the perfect embodiment of the Anglo-Saxon logic of domination: the merging of corporate greed, military violence, and moral hypocrisy under the flag of civilization. The so-called Banana Wars of the early twentieth century, stretching from the Caribbean to Central America, were not mere episodes of foreign policy but the industrialization of conquest. They marked the transition from territorial imperialism to economic colonization—a system where Marines replaced missionaries, and Wall Street replaced the Bible as the sacred text of the new faith.

Majfud situates this phenomenon in the continuum of the American frontier. After the continental expansion had exhausted its physical limits, the empire turned outward, driven by the same racial and economic impulses that had annihilated Indigenous nations and seized half of Mexico. The rhetoric of freedom traveled south, carried by warships and corporate contracts. In countries like Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic, the United States imposed a new order through violence disguised as stability, democracy, and protection. But as Majfud insists, what Washington called “protection” meant protection for American property, not for human beings.

The emblem of this system was the United Fruit Company—“El Pulpo,” as Latin Americans called it, the Octopus whose tentacles strangled entire nations. Its plantations dictated national policy; its railways and ports became instruments of occupation. When workers protested starvation wages or governments attempted to tax foreign profits, the Marines landed. The supposed goal was to preserve order, but Majfud shows that order meant submission. The “protectorates” established in this period were laboratories of imperial governance: puppet regimes ruled by local elites loyal to American interests and backed by military force. Majfud calls these rulers “the psychopaths of empire”—men trained to mimic civilization while serving barbarism, sociopaths who repressed their own people with pious speeches about liberty.

Among the most revealing voices of this era was that of U.S. Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, a soldier who became the empire’s most honest witness. Butler, who participated in interventions in Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Honduras, later confessed: “I spent 33 years being a high-class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer for capitalism.” He described how the Marines overthrew governments, installed dictators, and massacred resistors to secure profits for corporations like United Fruit, Standard Oil, and the National City Bank. In Haiti, Butler oversaw the occupation that dismantled the constitution, reintroduced forced labor, and transferred the national treasury to New York banks—all under the banner of civilization. For Majfud, Butler’s testimony is not merely an indictment of a system but a moment of moral awakening inside the machine. “The empire,” Majfud writes, “is most visible when one of its own dares to speak.”

The Banana Wars followed a precise choreography. A local government would attempt a reform—perhaps a minimum wage, a tax, or the regulation of foreign land ownership. The U.S. press, often financed by the very corporations at stake, would report “chaos” or “revolution.” The Marines would then arrive to “restore order,” and once the rebels were crushed, a treaty would be signed guaranteeing “free trade” and “stability.” Within weeks, the profits of the foreign companies would rise, and the country’s sovereignty would disappear. Honduras, invaded repeatedly between 1903 and 1925, became a protectorate without the name. Nicaragua was occupied for twenty years, its elections manipulated to install Anastasio Somoza, one of the psychopaths Majfud describes—a man who called himself the guardian of democracy while torturing and murdering his people with American support.

Majfud connects these events not to a specific policy but to a moral pathology: the conviction that domination is benevolence. The U.S. Marines were told they were spreading order and progress; the bankers believed they were bringing development; the presidents who authorized the invasions proclaimed that they were defending freedom. The result was a continent turned into a plantation, a geography of submission maintained by rhetoric. “The greatest success of empire,” Majfud writes, “is not to impose its will, but to make its victims speak its language.” The Banana Republic was born not only through violence but through imitation—when local elites internalized the empire’s moral inversion and reproduced it upon their own people.

Haiti offers one of the starkest examples. After the Marines invaded in 1915, they rewrote the constitution to allow foreign ownership of land, suppressing the revolution that had once inspired enslaved peoples across the world. The occupation built roads and schools, but for American companies, not for Haitians. Peasants who resisted were branded as bandits and executed. When the United States finally withdrew in 1934, it left behind a centralized army that would later sustain the Duvalier dictatorship—a regime that embodied what Majfud calls the “psychopathy of power,” the transformation of submission into cruelty. Similar patterns unfolded in the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Panama, each a reflection of the same logic: military occupation, corporate exploitation, local tyranny, and moral denial.

Majfud interprets this history as the natural evolution of the Anglo-Saxon frontier ethos. The Puritan settlers who once claimed to bring light to the wilderness now claimed to bring order to the tropics. The language of salvation remained intact; only the geography changed. “Every empire,” Majfud writes, “needs to believe that its violence is a mission.” The Marines who marched through Managua and Port-au-Prince carried the same spirit as those who crossed the Mississippi: a mixture of religious zeal, racial arrogance, and commercial appetite. The difference was that now the empire had perfected its instruments—it could destroy nations and call it reform.

The psychopaths Majfud denounces are not only the local dictators but the architects in Washington who saw the world as a marketplace and people as obstacles. They believed that the hemisphere belonged to them not by law but by nature. Their coldness was not madness but ideology—the belief that suffering was the cost of progress, that exploitation was civilization. In this sense, the Banana Republics were not deviations from the American ideal; they were its fulfillment. They made visible the essence of a system that confuses domination with destiny.

Majfud’s indictment culminates in a paradox. The empire that claimed to free the world from tyranny became the greatest producer of tyrants. The marines who landed to protect democracy created a generation of dictators trained in obedience and cruelty. The corporations that promised development left behind poverty, resentment, and ruins. And yet, the myth of benevolence survived. It continues to survive, transmuted into humanitarian wars, economic sanctions, and development aid. The banana may have lost its symbolic power, but the logic of the Banana Republic endures—the logic of empire without responsibility, conquest without conscience.

Smedley Butler’s confession remains the conscience of that era, the whisper of guilt inside the machine of virtue. “War is a racket,” he said, but in Majfud’s reading, the racket was not limited to war—it was the entire civilizational project that justified it. The Banana Wars were not accidents of policy; they were the essence of a system that cannot exist without lying to itself. The empire, Majfud concludes, is not defeated when it loses territory but when it loses its story. To reclaim truth, then, is the first act of liberation. And as long as nations continue to repeat the empire’s language—to call exploitation freedom and subjugation peace—the Banana Republic will never die; it will simply change its fruit.

An Era of psychological warfare and media manipulation

Majfud identifies a brief and tragic chapter in the continent’s modern history: the fleeting recovery of democracy in Latin America during the 1930s and 1940s, followed by its systematic destruction under the shadow of the Cold War. It was a rare moment when Washington looked away—distracted by its own crises, first the Great Depression, then World War II—and for the first time in decades, the nations of the South began to breathe. Reformist governments emerged, unions grew, literacy campaigns expanded, and people who had long been ruled by foreign corporations and local oligarchs began to believe that independence was not only a dream but a right. Yet, as Majfud warns, this interval of freedom was not permitted to last. Once the empire reawakened, it returned not with soldiers but with financiers, instructors, and intelligence officers. The result was one of the most paradoxical episodes in modern history: the birth of dozens of dictatorships in the name of defending democracy.

Majfud explains that during World War II, the United States needed Latin America not as a colony but as an ally. To secure raw materials and political loyalty, Washington temporarily tolerated progressive regimes. Presidents like Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico, Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, and Juan José Arévalo in Guatemala pursued nationalist and social reforms with unprecedented freedom. The war economy made U.S. capital less dominant; European powers were broken; and the region experienced a fragile window of autonomy. But beneath this brief tolerance lay the same old racial and economic contempt. The Anglo-Saxon establishment, Majfud notes, viewed these experiments not as legitimate expressions of democracy but as “dangerous outbreaks of immaturity”—childish nations playing at self-rule until the adults returned to restore order.

The war ended, and the empire returned with new weapons. The language of Manifest Destiny was replaced by the language of the Cold War. “Communism” became the new heresy, the new justification for the old interventions. Washington began to rebuild the mechanisms of control it had neglected during the global conflict. Through the creation of the School of the Americas, the CIA, and an expanding network of economic “assistance,” the United States financed, trained, and ideologically armed a generation of Latin American officers who would soon become dictators. Majfud calls them “the Cold War conquistadors”—men taught to see their own people as enemies, their patriotism as subversion, and their loyalty as submission to a foreign master.

The most emblematic of these reversals occurred in Guatemala. After years of military dictatorship, the election of Juan José Arévalo in 1945 and then Jacobo Árbenz in 1951 represented the culmination of a decade-long democratic awakening. Árbenz’s program was modest: land reform, social welfare, and the assertion of national sovereignty against the monopolies of the United Fruit Company, the symbol of U.S. corporate imperialism. But to Washington, this was intolerable. The same government that had tolerated Stalin as an ally against Hitler could not tolerate an agrarian reformer in Central America. Majfud highlights how the United Fruit Company, with deep ties to the Eisenhower administration, orchestrated a campaign of hysteria, branding Árbenz a communist puppet. The CIA responded with Operation PBSUCCESS—a textbook case of imperial subversion disguised as liberation. A fabricated “liberation army,” led by Carlos Castillo Armas, invaded from Honduras; radio broadcasts spread false reports of massive uprisings; and a sovereign government collapsed under the weight of lies.

Majfud sees in Guatemala 1954 the birth of the modern Latin American dictatorship: not the caudillo born from civil war, but the puppet born from strategy. The CIA not only destroyed a democracy—it invented a model. The success of this operation convinced Washington that covert manipulation was cheaper and more effective than open invasion. What followed was a continent-wide experiment in controlled repression. From Brazil in 1964 to Chile in 1973, from Uruguay to Argentina, the United States provided funding, training, and ideological justification for regimes that called themselves “national security states.” These regimes tortured in the name of freedom, censored in the name of truth, and disappeared thousands in the name of order. The same generals who studied democracy at American academies returned to destroy it in their own countries.

The fall of Árbenz also set in motion another historical reaction: the radicalization of Latin American youth. Among them was a young Argentine doctor named Ernesto Guevara, who had witnessed the coup firsthand while traveling through Guatemala. Majfud interprets this moment as a turning point in hemispheric consciousness. The betrayal of Guatemala taught Guevara and many others that peaceful reform under U.S. hegemony was impossible. The Cuban Revolution, born a few years later, was in many ways the child of 1954—a rebellion not only against the local oligarchy but against the imperial lie that democracy could coexist with dependency. Fidel Castro’s victory in 1959 was, to Majfud, both a continuation of and a response to Washington’s own hypocrisy. It forced the empire to confront a version of Latin America it could no longer control through illusion.

The reaction was swift and predictable. The same logic that had overthrown Árbenz now sought to crush Castro. In 1961, the CIA organized the invasion of Cuba by exiled mercenaries trained in Guatemala—the same ground where ten years earlier it had rehearsed its first coup. The Bay of Pigs invasion became a spectacular failure, exposing the limits of American omnipotence. But for Majfud, its significance lay less in the military fiasco than in the moral blindness it revealed. The empire could not comprehend why its rhetoric of liberation no longer seduced the oppressed. The Cubans, like the Guatemalans before them, refused to accept the role of grateful victims. In the eyes of Washington, their defiance could only be madness or treason. In the eyes of history, it was dignity.

Majfud connects this cycle of hope and betrayal to the deeper pathology of empire. The United States, he argues, cannot tolerate autonomous democracy in its periphery because its own myth of exceptionalism requires the existence of dependents. When Latin America governs itself, it ceases to serve as the empire’s mirror of moral superiority. Thus, every democratic awakening must be framed as a threat—first to commerce, then to security, and finally to civilization itself. The rhetoric changes, but the structure of fear endures. In the nineteenth century, the empire feared “the savage”; in the twentieth, “the communist”; in the twenty-first, “the terrorist.” In each case, the Other justifies the empire’s control.

By the end of the 1960s, almost every Latin American democracy born during the wartime interlude had fallen. Guatemala’s reformers were dead or exiled; Brazil’s generals ruled by decree; Argentina was under military control; Uruguay’s prisons overflowed with political prisoners; Chile’s future teetered on the edge of intervention. Washington called it stability. Majfud calls it regression—the restoration of the frontier mentality through modern technology. The CIA replaced the cavalry; the torture chamber replaced the reservation; the economic embargo replaced the bayonet. The method changed, but the faith remained: that the world must be governed by the chosen, and that disobedience is sin.

Yet Majfud does not end this chapter in despair. He insists that each cycle of repression produces its opposite. The same dictatorship that silences one generation gives birth to another that remembers. The Guatemalan coup led to the Cuban Revolution; the Cuban Revolution inspired the liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s; and even the failed revolutions of those decades planted seeds of resistance that survive beneath the surface of contemporary politics. The empire’s greatest weapon—its ability to disguise domination as virtue—is also its greatest weakness, for once the disguise falls, its power begins to dissolve. “The frontier,” Majfud writes, “is a lie that needs constant violence to survive. And every lie, like every empire, eventually runs out of breath.”

Thus, the story of Latin America’s lost democracies is not only a tragedy but a diagnosis of imperial fragility. The interlude of freedom during the 1940s revealed what was possible; its destruction revealed what the empire feared most: nations capable of governing themselves, peoples who no longer needed to believe in the mythology of protection. The history that followed—from Guatemala to the Bay of Pigs—was not merely a Cold War drama but the repetition of an ancient pattern: the empire striking back at the very freedom it claims to defend. In Majfud’s hands, it becomes a parable about the cost of innocence and the price of awakening. The hemisphere’s tragedy is not that it was conquered, but that it was taught to call its conquest peace.

The role of the CIA: the pen and the sword

According to Majfud, the CIA is not merely an intelligence agency but a central mechanism of an empire that learned to mask conquest behind new vocabularies of virtue. His argument is unflinching: after World War II, the United States did not abandon its old racial and colonial logic—it simply changed the words. Where the 19th century invoked the “savage” and the N-word to justify slavery, land theft, and genocide, the 20th century replaced those terms with “communism.” The mission was the same; only the banner was new. Under this substitution, the CIA became the modern conquistador, extending the “savage frontier” across Latin America with the same moral certainty that had once sanctified Manifest Destiny.

Majfud insists that this linguistic metamorphosis was not accidental but strategic. When racism became publicly unacceptable after the defeat of Nazi Germany, the empire could no longer speak the language of racial superiority. It needed a new myth that could rally domestic support and provide moral cover abroad. “Communism” became that myth—a universal enemy flexible enough to include democratically elected leaders, poor farmers demanding land reform, and priests preaching liberation theology. The CIA, armed with money, media, and manipulation, served as the invisible hand transforming that myth into reality.

In Guatemala in 1954, the Agency orchestrated the fall of President Jacobo Árbenz, who had dared to challenge the United Fruit Company’s vast holdings. The campaign painted Árbenz not as a nationalist or reformer but as a communist threat to hemispheric security. Majfud sees this as one of the first major acts in a new linguistic war: freedom versus communism was the updated version of civilization versus barbarism. The bombers that roared over Guatemala City carried not just explosives but words—the words that would make the crime sound like salvation.

The same script was repeated in Brazil in 1964, when João Goulart was deposed for proposing modest social reforms. CIA cables and corporate memos show a perfect alignment of interests between Washington, multinational corporations, and local elites. Once again, the accusation of communism provided the pretext for repression. What was really being defended, Majfud argues, was not democracy but hierarchy—the old racial and economic order dressed up in Cold War rhetoric. The military dictatorship that followed was presented to the world as a bulwark of liberty, even as it tortured, censored, and murdered in the name of that liberty.

Chile’s tragedy in 1973, with the overthrow of Salvador Allende, marks for Majfud the full maturity of this imperial vocabulary. CIA-financed strikes, propaganda, and economic sabotage paved the way for General Pinochet’s coup. Washington declared victory for democracy while celebrating the disappearance of the democratic process itself. Majfud calls this “the perfect inversion of meaning,” a triumph of the word over the world. Just as the slaveholders of the past had invoked “freedom” to defend slavery, the modern empire invoked “democracy” to justify dictatorship. The result was the same structure of domination, now sanitized by the language of the Cold War.

In Bolivia, the CIA’s pursuit and execution of Che Guevara epitomized this moral inversion. The operation was sold as a defense against communist subversion, yet it was, in essence, the ritual killing of an idea—the idea that the oppressed could resist. Majfud interprets the photograph of Guevara’s corpse, displayed by his captors like a trophy, as a modern echo of colonial rituals: the public exhibition of the defeated “enemy of civilization.” What had changed were the uniforms and the words, not the logic of conquest.

The Nicaraguan Contras of the 1980s brought this pattern to its grotesque conclusion. Trained and funded by the CIA, they committed atrocities while being described in Washington as “freedom fighters.” Majfud underlines the cynical genius of this rebranding: by calling violence “defense” and terror “liberation,” the empire not only justified its crimes but erased them from memory. The Iran-Contra scandal, with its labyrinth of secret funding and drug trafficking, revealed a deeper truth—that the CIA had evolved into what Majfud calls a “parallel government,” unbound by law, morality, or democratic oversight. It was, he writes, “the natural heir of two centuries of Anglo-Saxon fanaticism—self-righteous, expansionist, and incapable of seeing the other as equal.”

Majfud’s critique goes beyond politics. He sees in the CIA’s operations a cultural project aimed at shaping consciousness itself. Through propaganda campaigns, covert media influence, and the funding of intellectual elites, the Agency helped construct a worldview in which U.S. intervention always meant salvation. The Operation Mockingbird of the 1950s became the algorithmic manipulation of the 21st century. The method changed, but the purpose remained: to create a world where power defines truth. The empire, Majfud writes, no longer needs to invade with armies when it can occupy the mind.

He highlights a chilling continuity between the Puritan settlers and the modern intelligence officer. Both act with a sense of divine mission, both believe their violence is redemptive, and both are driven by an unexamined conviction of moral superiority. When former CIA Director Mike Pompeo declared, “We lied, we cheated, we stole,” and called it “the glory of the American experiment,” Majfud saw not a confession but a celebration—a moment when the mask slipped, revealing the old face of the frontier beneath the polished language of democracy.

In Majfud’s reading, the CIA is not an anomaly within American democracy; it is its logical expression. The same empire that once sent soldiers to kill “savages” now sends agents to fight “communists” and “terrorists.” The vocabulary shifts, but the structure endures: the United States as chosen nation, the rest of the world as its moral testing ground. What changes is only the justification—the myth that makes domination feel like destiny.

Ultimately, The Wild Frontier is not just a history of interventions but a study of language as a weapon. Majfud demonstrates how a single word—first “savage,” later “communist”—can transform aggression into virtue, racism into patriotism, and theft into freedom. The CIA, in his analysis, stands as both agent and symbol of this transformation: a machine built to rewrite reality in the empire’s image. And yet, Majfud insists, the empire’s tragedy is spiritual as much as political. “All the weapons in the world,” he writes, “cannot subjugate dignity.” The frontier, after all, is not endless; it ends where words lose their power and the truth begins to speak again.

A project for the New American Century

In modern phase of the hegemonic superpower, bayonets gave way to microphones, and coups were launched not only from barracks but from television studios and corporate boardrooms. The 1970s and 1980s marked a new sophistication in the old art of domination. Washington no longer needed to invade directly; it could destabilize, manipulate, and rewrite reality itself. The empire had learned that the most efficient conquest is not of territory but of perception. In this new frontier, the CIA and its allies in the media and financial sectors became the architects of invisible wars—wars fought in the name of freedom, masked by the language of democracy, and broadcast as truth.

Majfud traces this evolution through two of the most emblematic operations of the twentieth century: Operation Mockingbird and Operation Condor. The first, created in the 1950s, institutionalized the manipulation of information. Journalists, editors, and cultural figures across the Western Hemisphere were recruited or coerced into repeating Washington’s script. The goal was not only to censor inconvenient facts but to fabricate a moral universe where the empire was always virtuous and its victims always guilty. The Cold War provided the perfect moral alibi. “In the new era,” Majfud writes, “the bullet was replaced by the headline.” The empire no longer had to silence; it could drown truth in noise. This system of psychological warfare, he argues, extended far beyond the press. Universities, publishing houses, and even religious institutions became channels for propaganda disguised as enlightenment.

Operation Condor, born in the 1970s, was the violent counterpart of this cultural machinery. It unified the intelligence services of the Southern Cone—Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil—into a single transnational apparatus of repression, financed, advised, and coordinated by the CIA. Majfud calls it “the globalization of terror before globalization had a name.” Tens of thousands were tortured, disappeared, or exiled. The dictators who carried out these crimes—Videla, Pinochet, Stroessner, and others—believed themselves to be soldiers of civilization, defending Christian values and Western freedom. Washington rewarded them as allies. The same empire that condemned tyranny in Eastern Europe celebrated it in Latin America, as long as the tyrants protected the flow of capital. Majfud sees in this double standard the moral DNA of empire: a capacity to proclaim virtue while practicing horror.

But the frontier of manipulation did not end with ideology. In the 1980s, the empire refined its methods again through a fusion of covert warfare and organized crime. The Iran-Contra affair exposed how the CIA financed and armed the Contras, a counterrevolutionary army in Nicaragua trained to overthrow the Sandinista government. Majfud presents this as one of the most cynical chapters in modern history: terrorists rebranded as freedom fighters, paid with money obtained through the illegal sale of weapons to Iran and through the trafficking of drugs into the United States itself. The same agency that claimed to defend American youth from narcotics was using cocaine profits to finance death squads abroad. “The empire,” Majfud writes, “was no longer only exporting violence; it was importing its own corruption.” The war on drugs became another mask, a moral crusade concealing economic and geopolitical control.

The Contras were not an exception but the continuation of a pattern that stretched from Guatemala 1954 to Chile 1973. The empire needed enemies to justify its existence, and when those enemies did not exist, it created them. The CIA trained mercenaries and paramilitaries who burned villages, raped women, and assassinated teachers—all under the flag of liberty. In Majfud’s analysis, this moral inversion reached its grotesque climax when the same propaganda that once demonized “communists” began to demonize “terrorists.” The names changed, the targets changed, but the logic endured. Violence, if carried out by the empire or its proxies, was called security. Violence by others was called evil.

Majfud sees the transition from the Cold War to the neoliberal era as the digitalization of the frontier. The empire’s new weapons were no longer only rifles and spies but cameras, markets, and social media. The control of perception, perfected during Operation Mockingbird, now reached planetary scale. “Reality itself,” he writes, “became a product to be sold and consumed.” The twenty-first century interventions in Venezuela and Bolivia followed this formula to perfection. When Washington failed to control these nations through diplomacy or economic pressure, it turned again to the old tools of chaos: disinformation, financial warfare, and the orchestration of coups under democratic disguises.

In Venezuela, the coup attempt of April 2002 against Hugo Chávez exposed how modern interventions functioned. Corporate media channels broadcast falsified footage of government repression while private business elites coordinated strikes and street violence. A group of military officers, backed by the U.S. embassy and regional allies, kidnapped the president and installed a self-proclaimed “transitional government.” Within forty-eight hours, massive popular mobilization and loyal soldiers reversed the coup. Yet the narrative in Washington and much of the Western press portrayed it as a victory for democracy rather than its negation. Majfud interprets this episode as the digital echo of Guatemala 1954—an old script replayed with new technology. The lie remained the same; only the medium had changed.

Seventeen years later, in Bolivia, the same pattern unfolded. The 2019 coup against President Evo Morales—justified through allegations of electoral fraud amplified by international media and the Organization of American States—was, in Majfud’s view, another product of this imperial algorithm. When Morales’s government defied U.S. corporate interests in lithium and hydrocarbons, the familiar chorus began: democracy was in danger, the elections were rigged, and intervention was necessary. A coalition of military officers, conservative politicians, and religious extremists seized power amid violent repression. Once again, Washington applauded. Once again, the global media sanctified the usurpers as defenders of freedom. Once again, the frontier moved forward without crossing a border.

Majfud insists that these modern coups are not relics of the past but expressions of a perfected imperial intelligence—one capable of manipulating consciousness itself. In his analysis, the empire’s greatest innovation has been its ability to internalize control. Nations no longer need to be occupied when their elites think like occupiers and their citizens consume the empire’s fears as entertainment. “Operation Mockingbird never ended,” he writes. “It simply learned to sing in a thousand voices at once.”

The connection between propaganda, terror, and finance—visible in the Contras, the narcotics trade, and the corporate media—reveals, for Majfud, the moral symmetry of the modern empire. It fights corruption by funding it, combats terrorism by creating it, and defends democracy by destroying it. What began as the frontier’s violent expansion across the land has become a frontier of information and illusion, expanding endlessly through invisible means. In this system, truth itself becomes a casualty, and freedom becomes the empire’s most effective disguise.

Majfud concludes that Latin America’s struggle against these modern interventions is not merely political but existential. It is the struggle to recover reality from the empire’s narrative. From Operation Condor to the coups of the twenty-first century, the pattern remains unbroken: domination masked as salvation, chaos sold as order, and the victim transformed into the aggressor. The frontier, once carved with guns and maps, is now drawn with algorithms and headlines—but it is the same frontier, animated by the same belief that one race, one nation, and one truth must rule them all. The resistance, therefore, must begin not only in the streets but in the mind, where the empire first builds its invisible walls.

Conlcusion

In The Wild Frontier: 200 Years of Anglo-Saxon Fanaticism in Latin America, Jorge Majfud constructs a panoramic vision of domination, resistance, and myth that stretches from the genocidal wars of conquest to the covert interventions of the twenty-first century. The story begins with the land—where the ideology of expansion was first sanctified—and moves through the sea and the air, tracing how the same moral logic reinvented itself through centuries. What began as the violent expansion of settlers across the continent evolved into corporate imperialism, covert warfare, and the colonization of minds through propaganda. From the genocide of Native peoples to the coups of the CIA, Majfud sees not a succession of events but a continuous project: an empire sustained by its need to believe that its violence is virtue.

The frontier, in Majfud’s view, is not a geographical boundary but a psychological and moral system. It is the frontier of self-deception—where conquest calls itself freedom and theft calls itself civilization. The same Puritan zeal that once justified the extermination of Indigenous nations reappeared in the language of the Cold War, when the empire declared a new holy mission to defend the world from communism. After World War II, as Washington turned its gaze outward again, the old racial logic reemerged in new forms. During the war, Latin America had experienced a rare interlude of democracy. Nations long suffocated by dictators and foreign monopolies rediscovered their voices. Mexico’s Cárdenas nationalized oil; Brazil’s Vargas expanded labor rights; Guatemala’s Arévalo launched social reforms. But these experiments in sovereignty were tolerated only because the empire was distracted. Once the war ended, the tolerance ended too.

The return of Washington’s attention brought the return of control—this time more subtle, more global, and more efficient. The language of liberty was replaced by the language of fear. Communism became the universal enemy, the moral key that unlocked every intervention. The School of the Americas and the CIA became the new temples of empire, training Latin American officers not to defend their countries but to defend Washington’s interests against their own people. These men—Majfud’s “Cold War conquistadors”—were the children of a psychological empire. They learned to see dissent as subversion, nationalism as treason, and repression as duty.

Guatemala 1954 became the prototype of this new imperial architecture. A reformist government, led by Jacobo Árbenz, sought modest land redistribution and independence from the United Fruit Company—a corporation so entangled with Washington that its board members and the CIA director shared family and financial ties. The company launched a campaign branding Árbenz a communist. The CIA orchestrated a coup under the pretext of liberation. Fake radio stations, fabricated reports of rebellion, and a mercenary invasion from Honduras toppled a sovereign democracy. What followed was decades of slaughter under successive dictatorships. The empire called it a triumph of freedom. Majfud calls it the invention of the modern puppet state.

From Guatemala, the model spread. The dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s—from Brazil to Chile, Argentina to Uruguay—were not spontaneous eruptions of tyranny but components of a hemispheric strategy. Operation Condor coordinated their intelligence and terror networks, turning the continent into an open-air prison for its thinkers, teachers, and students. The empire financed, trained, and directed them in the name of defending the West. What it created instead was a machinery of disappearance—a technological extension of the frontier’s oldest logic: eliminate what resists, and call it order. The victims were branded terrorists, the torturers patriots, the silence patriotic duty.

But every act of domination produces its own counterhistory. The fall of Árbenz inspired a young Ernesto Guevara, who saw in the destruction of Guatemala the impossibility of peaceful reform. His journey from observer to revolutionary, from Guatemala to Havana, was the moral inversion of the empire’s project. The Cuban Revolution was not merely an act of rebellion; it was the response of a continent that had been told it was incapable of dignity. Its triumph in 1959 marked the first time in modern history that a Latin American nation defied Washington and survived. The response came swiftly: embargoes, sabotage, assassination attempts, and in 1961, the Bay of Pigs invasion—a recycled script, born in Guatemala, restaged in Cuba. When the invasion failed, it exposed the empire’s arrogance and its inability to understand resistance not as foreign manipulation but as human will.

After Cuba, the empire adapted once more. If direct invasion failed, covert war would continue. The 1970s brought Operation Condor’s assassins; the 1980s brought the CIA’s proxy armies. In Nicaragua, the Contras—financed through illegal arms sales and cocaine trafficking—became the new missionaries of freedom, committing massacres in the name of democracy. Smedley Butler, the Marine general turned whistleblower decades earlier, had already defined the system with brutal clarity: “War is a racket.” For Majfud, the Contras were proof that the racket had evolved; it was now transnational, sanitized, and televised. The CIA funded terrorism while declaring a war on terror, and the world believed because the media repeated it. Operation Mockingbird, conceived in the 1950s, had matured into a global chorus: newspapers, networks, and cultural institutions that framed imperial violence as humanitarian duty.

Majfud calls this the digitalization of the frontier—the transformation of conquest into narrative. The United States no longer needed to occupy nations physically when it could occupy their imagination. In Venezuela, the 2002 coup against Hugo Chávez unfolded on television screens before it unfolded in the streets. Corporate media declared his resignation while he was being held captive, legitimizing the coup as if it were a democratic correction. Within two days, millions of Venezuelans rose up and restored their elected president. The event revealed the empire’s new weapon: control of perception. The same formula reappeared in Bolivia in 2019, when Evo Morales was forced from power under accusations of electoral fraud later discredited by independent analyses. Washington applauded, media sanctified the coup leaders as liberators, and violence was again baptized as peace.

These modern coups are, for Majfud, the logical descendants of the frontier myth. The empire’s narrative remains unchanged: the barbarians must be tamed, whether they are Indigenous nations, socialist reformers, or environmentalists who dare to control their own resources. What has evolved is the technique. Where once the justification was race, it is now democracy; where once the weapon was the rifle, it is now information. The empire’s genius lies not in its brutality but in its storytelling—in its ability to make domination appear inevitable, even desirable. This is why, Majfud argues, propaganda has replaced theology as the moral language of power.

Operation Mockingbird’s heirs dominate digital networks; Operation Condor’s heirs control financial markets; the frontier survives, reborn as globalization. The United States no longer needs to colonize by force when debt, disinformation, and desire achieve the same effect. Yet even in this new configuration, the old pathology endures: the belief that the world exists to serve the chosen, that every rebellion is a threat to divine order. In this sense, Majfud’s “wild frontier” is not history—it is the present.

The pattern is circular and tragic. Each time Latin America rises in hope, the empire rediscovers a new language of fear. Each time it claims to defend democracy, it extinguishes it. And yet, the story refuses to end in despair. Majfud insists that truth, though fragile, has the same persistence as resistance. Every coup breeds memory; every propaganda campaign eventually exposes its lies. From the ruins of Guatemala to the defiance of Havana, from the graves of the disappeared to the streets of Caracas and La Paz, the voices of the silenced return, refusing to forget. The frontier, he reminds us, is not endless. It ends where conscience begins.

In the end, the history of the Americas is the history of that confrontation: empire and dignity, domination and memory, myth and truth. The weapons change; the arrogance remains. But so does the will to survive. Majfud’s final lesson is that the empire’s greatest power—the ability to disguise its violence as virtue—is also its greatest weakness, for when the disguise falls, the empire stands naked before the world, revealed not as destiny, but as fear. And fear, no matter how powerful, cannot govern forever.

Intellectual and Philosophical Contexts

The Moral Frontier: Ethics and Critical Consciousness in Modern Thought

The work of Jorge Majfud resonates with several major traditions of critical thought, extending and transforming them through a distinctly moral-philosophical lens. His writing situates the frontier not merely as a historical or geopolitical concept but as a moral and psychological condition of modernity itself. Through this lens, he reframes the theories of Fanon, Said, Foucault, Mignolo, Arendt, Martí, and others into a coherent meditation on power, violence, and conscience.

Like Frantz Fanon, Majfud exposes how violence is not an accidental feature of the modern world but one of its founding principles. Modernity, in this sense, is inseparable from the colonial project that gave birth to it. Yet while Fanon sees revolutionary action as the necessary path toward liberation, Majfud turns inward, seeking emancipation through the cultivation of moral and historical consciousness. Violence, he suggests, can only be transcended when societies confront their own complicity—when they recognize that the oppressed and the oppressor are both dehumanized by the same system.

His analysis also echoes Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism, revealing how Western identity was constructed through narratives of otherness. But Majfud expands Said’s framework beyond the East–West binary to encompass the entire hemisphere. In his reading, the Americas themselves became the first great laboratory of alterity, where Indigenous and African peoples were cast as civilizational foils against which the West defined its own innocence. The frontier thus emerges as a global discourse of exclusion and representation, a symbolic geography that shaped the modern imagination of power.

In dialogue with Walter Mignolo and Aníbal Quijano, Majfud also situates his thought within the broader tradition of decolonial theory, recognizing that modernity and coloniality are two sides of the same historical process. Yet he departs from purely theoretical approaches by infusing his critique with literary and ethical sensibility. His writing does not merely expose epistemic violence—it transforms it into moral reflection, translating complex theoretical ideas into accessible meditations on conscience and responsibility.

This moral dimension also marks his engagement with Michel Foucault. Like Foucault, Majfud understands that power produces knowledge, morality, and the very categories through which reality is perceived. The frontier, in his interpretation, is one such disciplinary mechanism, defining what is considered “civilized” and what must be excluded as barbaric. But where Foucault maintains a genealogical distance, Majfud introduces an ethical demand. Knowledge, for him, is never neutral; it must confront its own complicity in the systems of domination it describes. His work transforms the study of power into a call for moral awakening.

Nowhere is this moral inversion more evident than in his reinterpretation of Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis. For Turner, the frontier was the crucible of American democracy, the place where freedom was reborn. For Majfud, it is precisely the opposite: the frontier represents the original moral rupture of the American project—a founding myth of innocence erected upon genocide and slavery. The frontier, rather than a symbol of progress, becomes the site of disavowal, where violence is rewritten as virtue and conquest as destiny.

Majfud’s ethical critique also resonates with Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the “banality of evil.” Like Arendt, he sees modern systems of violence as dependent not on cruelty but on moral distance. In imperial democracies, domination is often bureaucratic, rationalized, and technologically mediated. Violence no longer requires hatred; it simply requires obedience and detachment. His writing exposes the quiet mechanisms that allow societies to believe in their innocence while benefiting from oppression—a theme that runs throughout his interpretation of modernity.

At the same time, his thought is rooted in the humanist tradition of Latin America. He inherits the moral vision of José Martí, as well as the narrative sensibility of Eduardo Galeano and Rodolfo Kusch. Literature, for him, is not an ornament to theory but a form of ethical intervention—a means of reclaiming dignity from the margins. Through storytelling, irony, and moral reflection, Majfud transforms historical critique into a meditation on conscience. His prose seeks not only to reveal injustice but to awaken empathy, to recover a human voice from beneath the ruins of ideology.

The originality of Majfud’s contribution lies in this synthesis of structural critique and ethical introspection. He bridges the theoretical rigor of thinkers like Foucault, Said, and Fanon with the humanist pathos of Martí and Galeano, uniting critical theory and moral philosophy in a single narrative. The frontier, as he redefines it, becomes a moral and psychological metaphor for the modern condition—an endless expansion outward that mirrors an unexamined void within. Modernity’s drive to conquer new territories, he suggests, reflects a deeper emptiness of spirit, a refusal to confront the violence embedded in its own foundations.

By reintroducing conscience into the discourse of power, Majfud reframes decolonial thought as both a philosophical and spiritual endeavor. His work demands not only the deconstruction of ideology but the reconstruction of moral sensibility. What distinguishes his approach is a rare fusion of philosophical critique with moral empathy. He does not stop at exposing the structures of domination; he seeks to understand the psychological and spiritual mechanisms that allow societies to sustain them, the illusions that make oppression appear virtuous.